Once Major League Baseball announced that it would embark on a shortened 60-game season to work around the pandemic and put some sort of 2020 on the record, it probably should've started the paperwork on José Abreu's Most Valuable Player trophy.

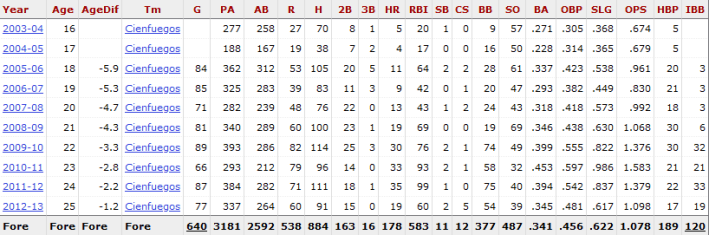

Before he defected from Cuba and joined the White Sox, Abreu turned every 90-game Serie Nacional season into a masterpiece, creating the otherworldly résumé that made Grantland call him "the best hitter you've never heard of" back in February 2012.

He was known as José Dariel Abreu back then, and he was still a year and a half away from leaving Cuba to ply his trade stateside. Nevertheless, it's a fascinating article to revisit now, because it does a pretty good job at assessing Abreu's potential.

He’s a first baseman at best and maybe a DH if and when he makes the big leagues. He doesn’t run well. His body is not exactly chiseled. His stats have been inflated somewhat by intentional walks (a league-leading 32 in 2009-10, and 21 last season) and hit-by-pitches (30 in 2009-10, 21 last season, though Abreu might have an easier time sustaining high HBP numbers than league-leading intentional walk totals in the majors). Even Abreu’s hit tool, while playable, might not be superstar-level.

“Is he Barry Bonds? No,” Forst said. “If you do a comprehensive survey of the clubs, they’d say he is not the best hitter on the planet.”

But?

“There are legitimate comparisons to Ryan Howard.”

So the wildly optimistic view is that it’s possible — not likely, but possible — that Abreu might be as good at — or better at — than Miguel Cabrera. And the more realistic and pervasive view is that he could hit like Ryan Howard, a star first baseman entering year one of a five-year, $125 million contract who has launched 262 homers over the past six seasons.

The stats likened him to Miguel Cabrera, perhaps better. A human correction downgraded him to Ryan Howard. Both worked for the White Sox's purpose, because both won MVPs.

And on Thursday, so did Abreu.

* * * * * * * * *

Just like postseason appearances, MVP awards aren't frequent for the White Sox. What they lack in abundance they make up for with regularity. Only four White Sox have earned the honor since its inception back in 1931, and they've been pretty evenly spaced apart. Nellie Fox won the first for the franchise in 1959, breaking the seal after sitting out the first 28 years. Dick Allen won the award 13 years later. It'd be another 21 years before Frank Thomas won the first of his consecutive trophies, and here comes Abreu 26 years after the Big Hurt's second.

Basically, once a quarter century, the franchise puts forward somebody who is worthy of the honor. What's striking is how considered their candidates are. Fox? Hall of Famer. Thomas? First-ballot Hall of Famer. Dick Allen had Hall of Fame peak, and he could eventually join them as attitudes evolve. There are no flukes, no flashes in the pan, no meteors who burned into dust. The White Sox respect the canon, and don't want to contribute anybody that might be written out of the game's history.

Or maybe they just haven't been good.

It's not quite that simple. The White Sox haven't hurt for quality hitters in between, but none of them could put it all together. Carlos Quentin came close, but his self-inflicted broken wrist severed the September he needed to seal the deal. Paul Konerko, Jim Thome and Jermaine Dye all posted numbers, but with limitations that sapped their value. Magglio Ordonez stuffed the stat sheet, but couldn't figure out how to lead the league in any categories during a period where records fell. Harold Baines had the same issue in a quieter era, although he lasted such an improbably long time that he -- or maybe Jerry Reinsdorf and Tony La Russa -- wore down enough opponents to unexpectedly propel him into Cooperstown.

The good-but-not-great individual performances during so-so team seasons relegated these players to "local legend" status, Baines included. Abreu appeared to be resigned to the same bin. He joined the White Sox mid-peak personally, but he caught the club at the start of the first of Rick Hahn's two rebuilds. From 2014 through 2019, Abreu averaged .293/.349/.513 with 30 homers and 102 RBIs, and the White Sox did not have a single winning season to show for it.

Abreu entered free agency after the season, and while it was abundantly clear that he wasn't going anywhere else, there was reason to question what kind of Abreu the White Sox would get from here. He led the AL in RBIs in 2019, but he also led the league in double plays, and he posted a sub-.300 OBP against right-handed pitching. If these were signs of decline, why wouldn't they be? He's a big-bodied 33-year-old with a huge strike zone.

The qualifying offer seemed like a reasonable reward for his contributions. The three-year, $50 million extension that followed resembled overkill and generated concern, locally and nationally. It would've been very White Sox to have individual loyalties interfere with team goals. In fact, it's happening right now with their manager.

* * * * * * * * *

At first base, the opposite happened. Abreu improved just about everything. OK, he still led the league in double plays, but he hit righties better, he ran better, and he fielded better. So much so, he led all AL position players in Baseball-Reference.com's WAR valuation despite the positional penalties a first baseman incurs. So much so, his biggest highlight might've been an infield single.

The mainstreaming of analytics has made it harder for first basemen to overcome skepticism about their limitations. Perhaps Abreu's surprising showing wouldn't have held up over the course of a 162-game season, at least enough to maintain an edge over a decent third baseman like José Ramirez, or a second baseman with positional flexibility like D.J. LeMahieu. There's probably a reason why first basemen won both MVPs for the first time since 2008.

While Abreu wasn't quite Vintage Albert Pujols in the field or on the basepaths, he contributed enough in both categories to preserve the margin. Eno Sarris made the sabermetric case at The Athletic.

Eno Sarris, baseball analytics writer: When you see raw emotion like Abreu showed when he won, it's awkward to talk about the numbers. The good news is there's a numerical case for the White Sox star. Ramirez may have had the higher Wins Above Replacement tally in some places, but Abreu was the better batter, and resting your case on always-iffy defensive metrics in a short season is probably folly. Use a different defensive stat, for example Statcast's Outs Above Average, and Ramirez shows as the 14th-best third baseman and Abreu in a tie for the second-best defensive first baseman in baseball. Well-earned hardware, well-earned tears.

It might have taken a special set of conditions for Abreu to end up on top, but to the extent that anybody could truly earn any standard regular-season honor over 37 percent of a season, Abreu did. It counts, just like the White Sox's winning season and postseason appearance count. Future triumphs might resonate more, but just like the first 10 years of his pro career, Abreu could only play the season presented to him.

And just like those years in Cuba, he crushed it.

* * * * * * * * *

For the first minute or so of Abreu's MVP existence, we could only see the top of his head. The longer he obscured his face from the camera, the more I thought about how he got here. His harrowing boat journey from Cuba to Haiti. Eating the first page of his fake passport on the flight from Haiti to the United States. Going 2½ years without seeing his son.

Basically, in order to understand his visually counterintuitive reaction to receiving the best news of his professional life, you'd have to put yourself in his shoes, and that's pretty much impossible.

MLB Network's Greg Amsinger had the tough job of giving Abreu room to process the emotions while keeping the show going. Through White Sox translator Billy Russo, Amsinger asked about the others in the room who were sharing the moment. Even that answer surprised. Abreu wheeled around and said "Mi abuela," pointing to the framed photo of his grandmother behind him, and started sobbing.

Abreu's composure ebbed and flowed over the course of the five minutes, but as Amsinger moved to wrap up the segment, Abreu collected himself to interject with specific gratitude. He started with the two people by his side -- his godfather, Emerson, and his agent, Diego Bentz. He also thanked the White Sox and Jerry Reinsdorf, followed by "all the Cuban players who came here before me and opened this path for me to be here," followed by God. The list might have been in reverse order of importance.

While Russo relayed the message, Abreu punched himself in the head in an attempt to make the feelings stop.

* * * * * * * * *

Abreu gathered himself by the time he talked to the Chicago media, after which he thanked more people. Some inadvertently reflected the less severe tribulations he's experienced. White Sox fans never really want to think about Adam Dunn or Manager Robin Ventura. They're reminders that the White Sox almost wasted Abreu's best years with talent and leadership that wasn't worthy of him. To Abreu, they're people to be thankful for.

Gratitude and respect never seem to leave the center of his being, to an extent that's sometimes difficult to believe. Not many people can submit "Now, my mom can really say that she has an MVP as a son, and she can keep saying that I am her MVP" into a press release without schmaltz or irony. Then again, not many people would react to an MVP announcement the way he did. There's a lot going on in there.

Everybody involved can be grateful that "Abreu's best years" extended into 2020, when the rest of the organization finally gave him a tailwind. If Abreu posts the same numbers for a White Sox team that goes 28-32, that award isn't his. That's just how MVP voting works when the competition's cases are that close.

The question from here his how much longer Abreu can sustain this revitalization. He wouldn't be the first White Sox first baseman came back to life after an apparent decline in his age-32 season. Konerko rejected time's initial attempt to drag him down and posted the two best years of his career at 34 and 35. He even opened his age-36 season with a world-wrecking two months before the decline set in for real.

Abreu is similarly beating back the odds, and one of his old comps in the process. He might share the title of "MVP" with Howard, but other connections are fraying. Howard won his at age 26, and was done as a productive everyday player at 31. Abreu wasn't allowed to play stateside until 27, and he's thrived at 33. He might not be able to surpass Cabrera in terms of lifetime achievement, but since Cabrera slowed down after 33, I wouldn't mind seeing Abreu beat him in longevity.

* * * * * * * * *

An MVP at this age adds a fascinating element to Abreu's legacy. If he'd talented enough to be named the league's best player in his mid-30s, what might he have accomplished if he were allowed to play Major League Baseball in his early 20s?

Flatten his record and cram together his MLB and Cuban League stats, and Abreu should pass 2,000 hits and 400 homers even with a disappointing 2021 season. Those numbers can't be taken at face value, but don't they have to be taken in some capacity? Abreu was legally prohibited from playing at the game's highest level. He did all he could around he circumstances, dominating lesser competition and succeeding immediately when he gained entry to the United States. That profile suggests he lost several years of stardom, and while 2020's schedule was unprecedented for MLB players, it was the the eighth year of counting stats that Abreu lost to a shorter slate. He also lost the entirety of his age-26 season while defecting.

Hall of Fame voters would have had to bridge a similar divide with Ichiro Suzuki, who also had to wait until 27 to test himself in Major League Baseball. He might've been a great pilot case for Abreu, except Suzuki played into his mid-40s, racked up 3,089 hits and became a no-doubt Hall of Famer on his American experience alone.

With Suzuki removing himself from the equation, the only similar cases are that of Negro Leagues players who had to bide time until the color barrier came down for good. Abreu's exclusion from the major leagues isn't the same stain on national history, but some precedent would seem to apply to somebody who was born on the wrong side of (geo)political circumstances.

It's too soon to entertain that discussion in detail, but it's a discussion this MVP encourages. Other things that would bolster the case: additional excellent seasons and awards, and some postseason heroics. The way Abreu tells it, he doesn't need anything more than his mom to motivate him, but more reinforcement can't hurt. It's more incumbent on the White Sox to step up their efforts to reinforce him, and the residual exuberance from Abreu's big moment should provide years of inspiration.

(Photo by Zach Bolinger/Icon Sportswire)