Every White Sox fan paying half attention to the 2020 season could tell you the most difficult catch made by one of their outfielders last year: Luis Robert's incredible diving catch right of center in Kauffman Stadium on Sept. 5.

But few might guess which outfielder came runner-up to Robert's effort. At least if he hadn't been mentioned in the headline.

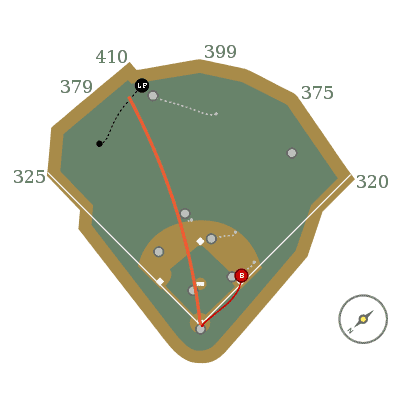

While Robert led the way in degree of difficulty by running down a fly with a 15-percent catch probability, Jiménez contributed his own five-star effort on this Bryan Reynolds line drive at PNC Park on Sept. 9, a mere four days later.

This one had a catch probability of just 20 percent. The pitch tracker shows a mistake, and Dane Dunning is bracing for an ugly outcome. Reynolds split the left-center gap, which wasn't great since Robert was positioned toward the right center. Only one man could possibly get the job done...

... and against considerable odds, that one man got the job done.

We've seen Jiménez yield to Robert even on fly balls well within his jurisdiction, and to amusing results. PNC Park's cavernous left-center gap -- and the shift deployed on the lefty Reynolds -- offered no such overlap between the outfielders, meaning that Jiménez had a chance to flag down a ball in the canyon without the threat of Robert approaching.

Given the freedom to fly, Jiménez didn't even have to leave his feet.

Jiménez hadn't made a catch that difficult before, and he didn't make one in the small sample size afterward. That makes it easy to write off as a fluke, but a couple of elements of his game explain how it was even possible. As awful as he looks in the field, it's not the fault of his top-end speed, which has been in the 60th-70th percentile in his time in the league.

It might also surprise you to learn that Jiménez finished tied for third in Statcast's outfield route metric with Mike Trout. He's fast enough, and he takes a decent line to the ball when tested. Once in a while, the stars align and those skills combine to create something beautiful.

* * * * * * * * *

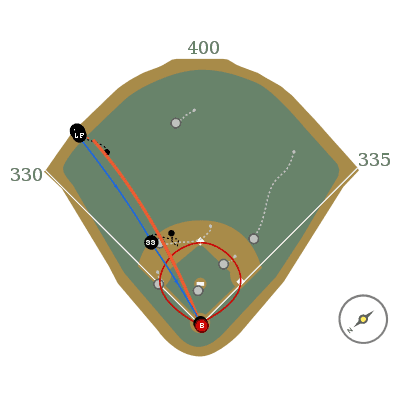

Five days later, Jiménez botched what should've been an easier catch, threatening a ninth-inning lead that Alex Colomé ultimately preserved for a key win over the Minnesota Twins. Byron Buxton opened the ninth inning with a hammered liner to left. It was a rocket at 108.9 mph, but Jiménez was positioned correctly.

The only problem was that his feet wasted no time taking him out of position.

While Statcast grades Jiménez's routes as above-average, and his reaction time is merely slightly below average, his burst metric -- the feet covered in the 1½ seconds after the initial jump -- is bottom five in the league.

Then you go back to the route leaderboard, and you see that four of the top six outfielders in that metric are deep in the hole at their positions, and Nomar Mazara -- who finished atop the route leaderboard -- is a hair below average himself. Alex Gordon is the only one whose route made up for pedestrian reaction and burst in his jump.

The players with the best route scores seem to be rewarded for their caution. Because they're slow to react in that first second or so, their initial moves are likely to be more precise than the guys who are quicker in moving in the general direction. My puppy is learning to play fetch, and Chief doesn't start running until the ball approaches a stop. Statcast would praise his route efficiency, but it'd slam him for his reaction and burst, and he'd deserve every bit of it.

Anyway, Statcast gave this a catch probability of 99 percent, because it only required Jiménez to move 30 feet in a little over three seconds. Unfortunately, as the numbers indicate, Jiménez can often make a mess of those first three seconds when they're all he has.

* * * * * * * * *

So let's go back to that first catch. Jiménez hauled in that drive in part because the ball was launched far enough away from him to give him no doubt about the kind of effort it'd require. PNC Park's dimensions allowed Jiménez to run full speed for several seconds without worrying about encountering a wall, and Robert's positioning removed that threat from the equation as well.

That's a very specific situation, and one Jiménez probably isn't going to encounter most of the time. The alleys aren't nearly as spacious in Guaranteed Rate Field, and like MSNBC, Robert pretty much owns the turf left of center. Jiménez is supposed to command everything toward the line. Again, he can show some authority when he's shaded toward the alley and he knows he has to run hard immediately ...

... but when he's less certain about direction and speed, it can get messy in a hurry ...

... especially if there are complicating factors like warning tracks and walls.

* * * * * * * * *

What's perhaps most frustrating about Jiménez in left field is that sometimes it works. Eleven days before his mishap on Buxton's drive, Jiménez flagged down a slightly softer version of the same line drive off the bat of Whit Merrifield. The read looks confident, he times the leap properly, and the start-to-finish product left the Royals booth wondering why his smooth effort didn't match the scouting report.

It'd almost be easier if he didn't make plays like this one, because then Rick Renteria wouldn't have felt compelled to leave him out in the ninth inning and risk giving up an inside-the-park homer to Buxton, and Tony La Russa won't have to wrestle with the same this year. The Sox could either set up a permanent caddy, or rotate him in and out of the DH spot, or DH him two-thirds of the time like Marcell Ozuna in Atlanta, crossing fingers for similarly sexy results. But with so many other bats struggling to stay out of DH or an even more entrenched corner at first, the White Sox are pretty much stuck with it for at least one more year.

There's a chance that he could improve enough to stick without question, because he did patch some of the biggest bugs over an atrocious first few months to be a more ordinary kind of liability. Further improvement remains within his reach. I just think it's outweighed by the likelihood that Jiménez is more or less this left fielder, with calm stretches interrupted by misplays on catchable flies at inopportune times.

His defense was always questionable during his prospect days, but it wasn't supposed to be this ugly. Then again, his frame hadn't filled out back then, either. Perhaps the added mass makes those uncertain first steps costlier than they used to be. He's not likely to get lighter or faster, so unless he can somehow bend time to cram four seconds of movement into three seconds of action, he's going to have to improve his instincts. After watching him figuratively and sometimes literally run in place over his first 1½ seasons, it's hard to tell which one is easier for him to realize.

(Photo by Kiyoshi Mio/Icon Sportswire)