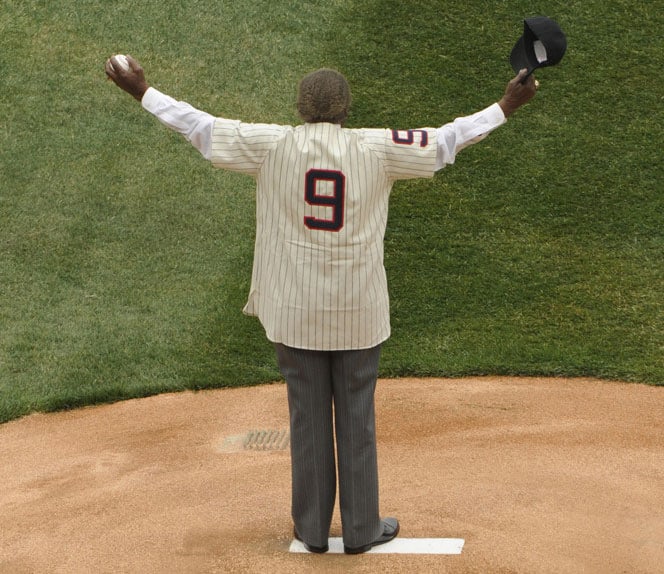

Hall of Fame election results seldom shock, but the snubbing of Buck O'Neil in 2006 stunned. The special committee to elect Negro League players in one fell swoop seemed designed to open a door for O'Neil, whose tireless work on behalf of the Negro Leagues and their icons made everything possible. Plus, he was one of just two candidates on the ballot who was still alive. Just about everybody wanted to see it happen.

Yet it didn't happen. Somehow, he didn't get the votes. O'Neil possessed the grace to speak at the induction on behalf of the 17 others inducted, but he died shortly after, and well before he'd get another chance to be considered for his own bronze plaque.

Supporters of O'Neil could console themselves by saying that the Hall of Fame needed Buck more than Buck needed the Hall of Fame, and while Joe Posnanski's account of the evening suggests O'Neil swallowed pounds of pain in order to keep the spirits of others aloft, the way he carried himself afterward made such consolation possible.

Minnie Miñoso, the other living member on that special Negro Leagues ballot, shared plenty of characteristics with O'Neil, particularly perseverance, a generosity of spirit, and a real joie de vivre. But when it came to falling short of induction, Miñoso made his heartbreak known.

His omission in 2006 was more understandable than O'Neil's, as voters were instructed to focus only on their Negro Leagues career, and Miñoso only played three years for the New York Cubans before Cleveland came calling. I'm guessing the intent was to keep Miñoso's MLB success from adversely affecting the cases of players who never got the chance to thrive in the majors. I don't think that gives the voters enough credit -- and if it accurately assesses the voters' inability to juggle multiple contexts, then they needed a smarter panel. Still, at least it made some sense, and unlike O'Neil, Miñoso would have other chances on a relatively regular schedule.

When the committees stiff-armed Miñoso in his next two appearances, that's when it started to take its toll, and Miñoso finally expressed frustration.

Truly, I'm hurt. You know why? Because I've seen so many guys -- and all of my respect is for them -- get inducted [into Cooperstown], but my records are better. And I played more years. That's what's breaking my heart. I go to these card shows, and most guys there are Hall of Famers. Some of them got in later, but what difference should there be?

This year, nobody was inducted [by the Golden Era Committee]? And you're really telling me that nobody had the quality to be [in the Hall of Fame]? C'mon. It's not just me. Tony Oliva, Billy Pierce, Luis Tiant … [The committee] should have considered Mike Cuellar, Richie Allen. Are you telling me these guys will never get in? I don't know what to say. […]

Don't tell me that maybe I'll get in after I pass away. I don't want it to happen after I pass. I want it while I'm here, because I want to enjoy it.

Those words are from an interview by Christina Kahrl published Feb. 26, 2015. Miñoso died three days later.

Imagine that interview taking place had Miñoso gained entry to the Hall of Fame in 2006, or 2011, or 2014. For a guy who defaulted to optimism, joy and gratitude, it's lamentable that his final interview caught him while he was stinging, rather than bursting with pride. The guy who led the league in HBPs 10 times shouldn't have been required to take one more for the team on his way out.

Sure, he didn't need the Hall of Fame. But he wanted it, he earned it, he deserved it, and at 90 years old (more or less), he lived long enough for everybody to come around on what he'd accomplished. The system failed him at the start of his career, but why did it have to fail him at the end of his life?

From that angle, Miñoso's election on Sunday hurts. It's unfair that the Hall of Fame has the luxury of hoisting plaques on its own timetable, and there's no real cost to the institution for tangling Miñoso in its bureaucracy. Whether the honor comes on time, sooner than expected or years too late, the HOF stamp still manages to matter, which can be the bad news.

* * * * * * * * *

That also makes it the great news. Miñoso might not be around to enjoy the victory lap, but his supporters could party with Miñoso's widow and son at Sluggers in Wrigleyville. The bar was Miñoso's home away from home, to such an extent that Miñoso apparently made himself comfortable back of house:

Only Miñoso's career and achievements were up for judgment, but everybody in his immense orbit can appreciate the validation, because so many people worked so hard to make it happen, and the bulk of them are still around. A lot of them work for the White Sox, who were tireless in their efforts over the years stumping for the legacy of their favorite person.

LISTEN: Sox Machine Podcast: Minnie Miñoso, Hall of Famer

And even if you've never been particularly invested in the quest for the Hall's belated appreciation of Miñoso, the stamp of approval makes it so much easier to spread his story. As proof, here are five 20th century players I probably wouldn't know a thing about if they weren't in Cooperstown:

- Ross Youngs

- Chick Hafey

- Eppa Rixey

- Travis Jackson

- Freddie Lindstrom

All of them were National League players whose careers rose and fall between World Wars. They won a batting title here and a World Series ring there, but I can't think of a reason why i would've encountered them outside of random Baseball-Reference.com pings. But because they're in the Hall of Fame , I can tell you that Rixey won nearly 300 games, that Hafey had a string of impressive batting averages, that Youngs died, well, young.

Think of that effect on somebody like Miñoso, whose effect on the game extended beyond round numbers. The greater baseball world was slow to recognize his role as baseball's first Black Latin player, dealing with prejudices stemming from the color of his skin and the language barrier. His home run totals were suppressed by the home park, which Miñoso compensated for with speed. He played fast and hard, pounding line drives the opposite way in Comiskey Park's spacious outfield and running like hell. His case required finesse, nuance and patience, understanding the three years he lost as baseball slowly opened the doors to non-white players, and the obstacles he faced once he arrived.

Miñoso's colleagues, fans and supporters have built the case year after year, showing how favorably he compared to Mickey Mantle, Ted Williams and others during the American League in the 1950s, then listing references like Orlando Cepeda and Tony Perez who pointed to Miñoso as the guy who first made it possible for players like them.

Everybody who's been beating the drum for Miñoso can take the next 200 measures off, because the Hall of Fame's marketing apparatus will take over from now through the next voting cycle. Another institution with a broader reach can educate the masses for a little while, and the museum can make it easier to find next to the fellow greats who might be better known. Eventually the buzz will die down and the locals will have to resume the bulk of the storytelling duties, but for Miñoso and everybody else involved, this is a rest well earned.

(Photo by Warren Wimmer / Icon Sportswire)