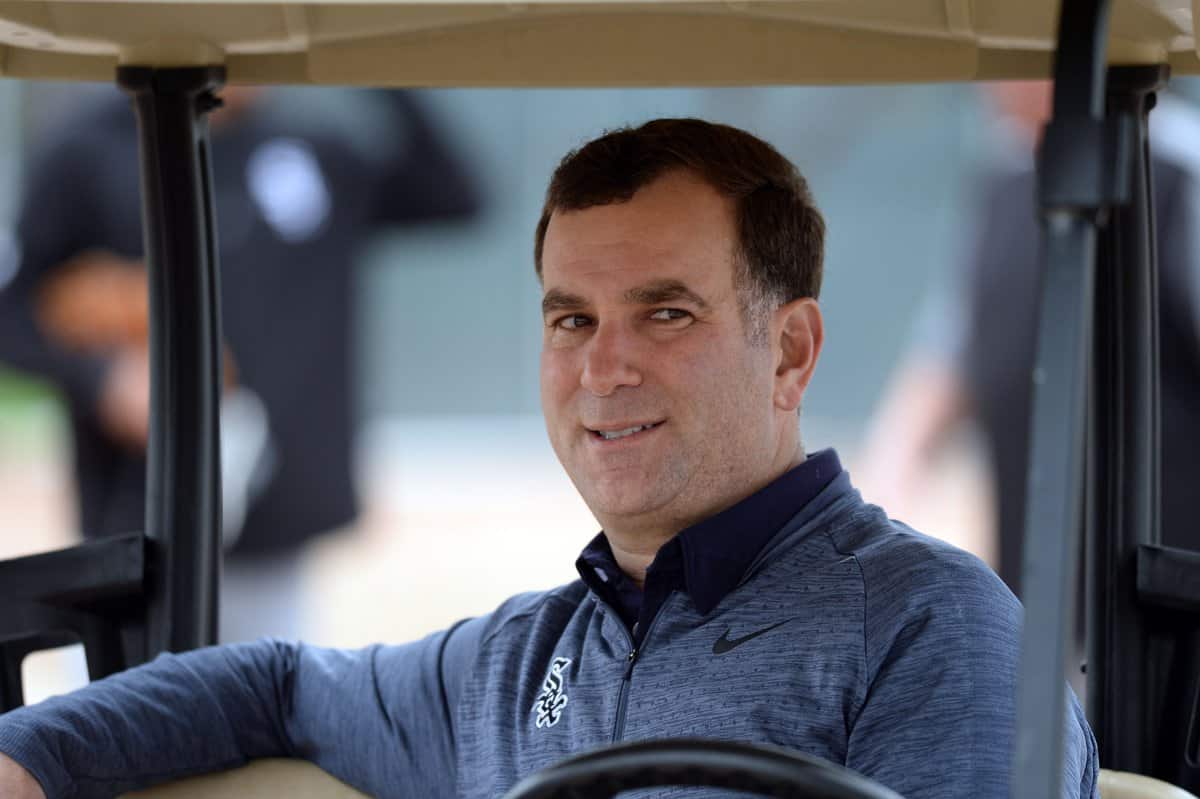

White Sox pitchers and catchers reported to spring training on Wednesday, and Rick Hahn spoke to the media for 35 minutes.

About 25 of those minutes were devoted to the Mike Clevinger domestic violence/child abuse investigation, and about zero of those minutes were satisfactory. Sure, there wasn't any way Hahn could emerge victorious, mostly because the White Sox's hands are mostly tied one way or another. But while Hahn maintained that the White Sox take the allegations of domestic violence and child abuse seriously, he didn't offer any sort of vision for what "taking it seriously" might mean if Clevinger were to be found partially or wholly culpable, which does nothing to reassure fans with direct personal connections to abusive relationships, or just a fan base that already thinks nothing of the White Sox's disaster planning.

Hahn tried to duck behind the joint policy's anonymity requirements whenever possible, including times where that wasn't even the question. James Fegan asked Hahn about what a White Sox background check comprises, and because Fegan's question included "why such a thing may not come up," Hahn only answered that part of the question before Fegan reiterated the larger question, "What does the process generally consist of?"

At another point, a reporter responded to Hahn pinning the White Sox's ignorance on anonymity by pointing out that the club could have theoretically found out about the subject of the investigation without ever knowing about the investigation itself (a Washington Post story from a few weeks ago said a police report was filed). Hahn could only offer, "Ideally, if we could've found that out, that would've been informative."

Stephanie Apstein of Sports Illustrated -- who might've been the aforementioned reporter if I kept the voices straight -- later asked a blunter question: "Are you frustrated with Mike for putting you in this position?" and Hahn's programming briefly locked up.

While the subject matter was miserable, it was illuminating to hear Hahn questioned (with follow-ups) by reporters who aren't conditioned to a White Sox front office that never faces consequences because Jerry Reinsdorf stopped caring.

For instance, I'm surprised that Hahn is so willing to remind everybody about how long he and Kenny Williams have been allowed to maintain their hierarchy, because their only really meaningful accomplishment happened so, so long ago.

“From a due diligence standpoint, we have had some success in past years – I’ve been here now, this is the start of my 23rd season, so I’ve been involved in a lot of background checks, a lot of evaluations of players’ makeup from outside the organization – we have had success at times in the past taking calculated risks on players that had, let’s say, immaturity issues with other organizations, bringing them in here, making them part of our environment and giving them a new opportunity to fulfill their potential,” Hahn said. “We probably don’t have that ring in ’05 without taking chances like that."

And sure, that's true. The Angels cut Bobby Jenks due to an alcohol problem, A.J. Pierzynski was so unpleasant the Giants non-tendered him, and Carl Everett's rejection of dinosaurs masked a whole lot of less amusing forms of unbalanced/unhinged behavior.

But 2005 was 18 years ago, before high-definition highlights and the modern form of social media (Facebook was limited to college students until 2006). If a 2005 White Sox form of Mike Clevinger fielded/dodged questions about -- and denied the allegations behind -- an investigation into domestic violence and child abuse like he did on Wednesday ...

... there would be no way for his accuser to issue her side of the story, and it'd probably fade away in time. Major League Baseball wouldn't have a designated policy to handle the specific sensitivities of domestic violence/child abuse for another decade.

But here in 2023, Olivia Finestead responded to Clevinger's comments through her Instagram account, followed by a 25-minute interview with Danny Parkins and Matt Spiegel on 670 The Score.

Somebody's lying here. It's also possible that everybody is lying to some degree, simply because the sheer volume of accusations makes it possible that some aren't true. It's a mess with no triumphant outcome.

But when I talk about Hahn and the White Sox failing to reassure on even the smallest of fronts, Clevinger immediately undermined Hahn's attempt to lead his signing toward humility, which Fegan captured in his story:

“We had several conversations at that time about what are we getting from a makeup standpoint,” Hahn said. “There certainly were some positives in terms of work ethic and focus and desire to win and compete and understanding of his own mechanics and efforts to improve, which are positives. But there were maturity questions. He’d admit that probably by his own volition. That’s what I was referring to in terms of we’ve had similar guys who have had reputational questions.”

Clevinger did not as readily acknowledge such issues.

“Oh, when I was like 20, 21? When I first got into pro ball?” he said. “I’d say so. Definitely. I’d say when I was a younger man jumping into pro ball, I was a little bit immature, for sure.”

No, that's not it. If they weren't referring to Clevinger's previous public relationship flare-up in 2019 when Clevinger was 28, they were referring to his suspension for flouting COVID-19 protocols and lying to his teammates in 2020, when he was 29.

Clevinger is now 32.

This is going to be exhausting, and it didn't have to be this way. What makes the White Sox's insufficient due diligence so glaring is that Clevinger wasn't signed for a minimal amount toward the end of the winter. Instead, the White Sox jumped the market to sign him, and judging from subsequent signings, they didn't appear to get any kind of dickhead discount that allowed them to sign Jenks and Pierzynski at professional lows for low, low prices.

Hahn expressed disappointment that the organization had to weather these accusations to open a spring training where everybody had their hands full putting the last nadir behind them ...

"I regret the fact that we're sitting here today talking about this. I understand why we're doing it, obviously we have to. But this is a year in which we have high expectations. We have a new staff that's trying to hit the ground running to help us fulfill those expectations. And we've got a heckuva lot of players in that clubhouse right now who feel like they have something to prove."

... but then he kept talking, and inadvertently emphasized that the White Sox could've dodged this whole thing by aiming higher.

"Frankly that was part of the appeal in bringing Mike in prior to all this. Prior to all this, he had something to prove as well. Here's a guy who historically has pitched, when healthy, like a guy towards the front of a rotation. At this point in his career due to injuries, you know he's not out there reaping the benefits financially of what a front-end starter gets, and here's a guy who could come in potentially with something to prove, a chip on his shoulder, to show he belongs, to be treated like the elite pitcher he has shown himself capable of being."

The White Sox had an overload of injured players who need to prove they're reliable. The solution typically isn't "another injured player who needs to prove he's reliable," but the White Sox are built different. It's just not a good different. Most of it isn't up to code. It should probably be condemned.