The White Sox open a series with the Baltimore Orioles tonight, and three games into the season, it seemed like White Sox catchers would have their hands full. And they still might, because the Orioles are 19-for-20 in stolen bases over their first 13 games.

That does represent a slowdown compared to the first two games of the season, when they went 10-for-10 on poor Reese McGuire and the Boston Red Sox. They haven't tried more than two steals in any game since, but maybe that's because Cedric Mullins is off to a slow start.

That's allowed the rest of the league to draw nearer. The Orioles now own a share of the league lead with the Guardians, who are 19-for-21. The White Sox are sixth in total steals with 13, but they've stolen the most bases for a team with a 100 percent success rate (the Phillies are next at 10-for-10).

The stolen base environment is still undergoing evaluations and experimentations, and I want to draw your attention to three articles about it.

Over at MLB.com, Mike Petriello looked at the situations where stolen bases are surging. Steals of third are way up. Beyond that, he says that the success rate shoots up once a baserunner draws at least one disengagement.

If [it's true that the steal success rate is down with zero disengagements], then it must also be true that success rate after one or two disengagements must be higher than they are on zero, and it really, really is. It is essentially the entirety of the uptick in stolen-base successes.

Stolen-base success rate, 2023

*On 0 disengagements: 73%

*On 1 disengagement: 81%

*On 2 disengagements: 100% (that’s a mere 4-for-4)All of which seems to mean that disengagements are valuable currency, and if so, drawing them might be a skill. It might be too early to say that some teams are prioritizing this where others are not -- surely this has more than a little to do with the identity of the runners on base and how often a team even gets on base -- but when you see the Guardians, Astros and Dodgers at the top of this list, maybe it’s not too early.

That makes the humble pickoff throw the subject of unprecedented consideration, and Lindsey Adler of the Wall Street Journal talked to economists who study game theory. They say randomization is key, but there's a catch: Humans generally suck at randomizing, and the pitch clock compresses the number of possible permutations. The only way pitchers can combat this is by returning the mound quicker.

“If the clock is under five seconds, it’s probably a good bet that they’re not going to use a pickoff attempt,” said Giants pitcher Alex Wood. “The guys who get back on the mound quickly, they’re going to have different hold times. Whether they hold the ball for three seconds or five seconds, they can use that to their advantage.”

The increased predictability of pitcher timing has emboldened the Yankees to take a short initial lead, then jump into their actual lead.

The technique is not without risk, and the Yankees are tied for the league lead in unsuccessful attempts with four. But they've also been safe 12 times, which used to be the old break-even point. If teams are able to reach the 75-percent threshold even after getting their average runners more involved, there's no telling what the numbers might look like at the end of the season.

Spare Parts

Steven Goldman made his name in the baseball blogosphere covering the Yankees, but you'd think he was a White Sox lifer when reading his disgust with the team after Gavin Sheets' non-error error on Wednesday.

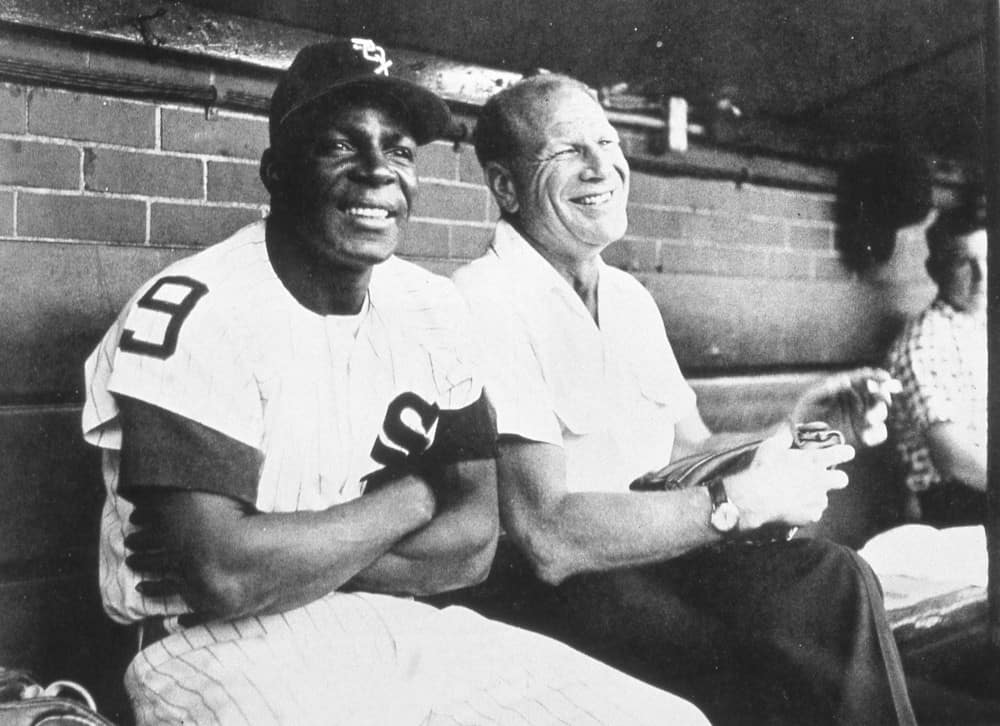

After Wednesday afternoon’s loss, the Sox are 5-8. This puts them on a pace for 100 losses. It is far too early to take their record seriously; in this century alone three eventual World Series-winning teams began the season with the same 5-8 record (the 2001 Diamondbacks, 2002 Angels, and 2021 Braves). And yet, this is a team that lacks identity, as it has lacked it for many years despite making the playoffs in 2020 and 2021. It has the look of a construction project that is perpetually unfinished. As an organization the White Sox invoke the Winston Churchill line about being adamant for drift.

The living embodiment of this tendency used to be Leury Garcia, who through no fault of his own became The Out the White Sox Loved to Play (soon to be a Broadway musical), but he was released at the end of spring training. He seemed permanent, and his being cut was such a seeming impossibility that it was like hearing the Chicago River had been drained. Today that symbol might be Gavin Sheets, a first baseman by training and talents who last year was forced to the outfield because with José Abreu, Andrew Vaughn, and (sometimes) Eloy Jiménez around there was too much competition for the first base and designated hitter spots. By the standards of an average defensive outfielder, Sheets looked very much like an early 17th-century Fassadenschrank cabinet, reputedly “a tour de force of cabinetmaking,” but not very much known for catching baseballs hit to its left or right. Still, lest this column seem too negative, let it be said that Gavin Sheets is a tour de force of cabinetmaking.

Speaking of woodworking, I'm happy to learn that I beat David Roth to describing Gavin Sheets as an armoire. He used the blooper as a way to cover all the ways the White Sox threw their bodies around over the last week.

On Sunday, the White Sox were a party both to Oneil Cruz's ankle injury—which was mostly the fluke-y result of a terrible slide—and the brawl that followed after catcher Seby Zavala said something to the writhing star that his Pirates teammates didn't appreciate. (This is the rude part.) A day later, one of Chicago's ostensibly glove-first utility players, Hanser Alberto, glitched out during an extravagantly botched rundown, which led to a sprained knee that could keep star shortstop Tim Anderson on the shelf for a month. Taken on its own, it is the sort of annoying but not necessarily season-altering injury that could (and does) happen to any big-leaguer, and which has happened to Anderson with dispiriting frequency over his career. Watch the play in question, though, and it's clear that we are dealing in Some Real White Sox Shit.

Major League Baseball's fight with Diamond Sports Network escalated when the Bally's owner stopped paying the Guardians, Twins and Diamondbacks for broadcast rights while still airing their games.

Diamond does not dispute it has the money to pay the tens of millions of dollars it owes the three teams, but argues bankruptcy law allows it to restructure the contracts to better reflect market value. When Diamond signed many of the team deals, it was before the accelerated pace of cord-cutting, a trend that helped land the company in bankruptcy court.

Diamond is arguing it should be allowed to rip up the contracts and rewrite them to reflect the lower number of cable subscribers now versus when the deals were originally inked.

MLB reacted with scorn to the argument that Diamond could just slice off the amounts owed the three teams.