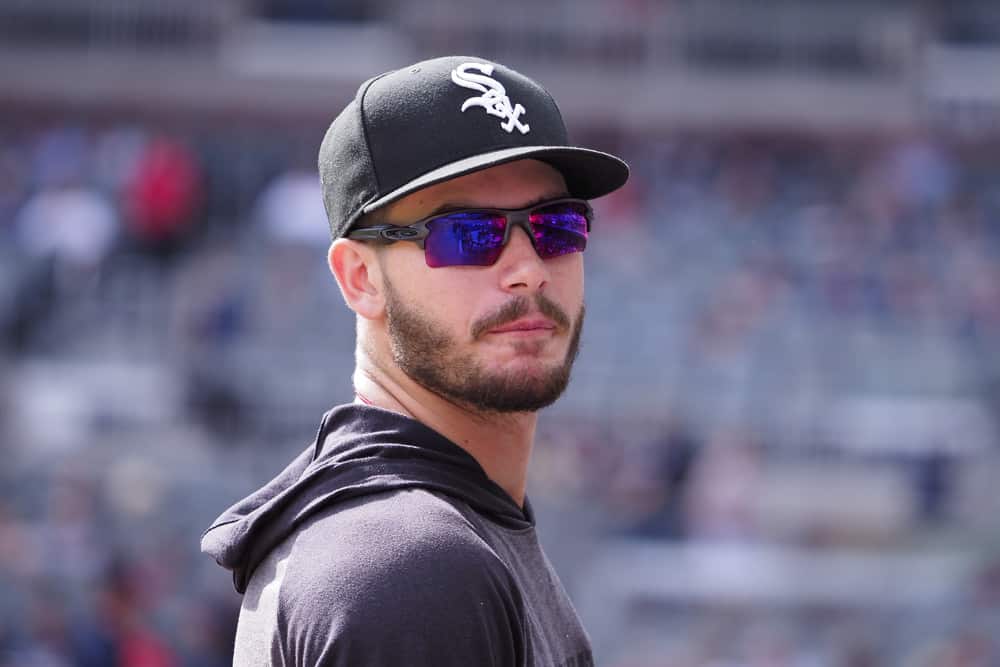

Walking away from talking to Dylan Cease after a spring training start, stalwart AP reporter Jay Cohen said idly, "That guy talks like someone who knows he's going to be really good this year."

It was late March of 2022, and later this year Cease would come a pitch away from a no-hitter, a man away from a Cy Young award. It would be fun to say that Jay was and is a genius, but also Dylan always talked this way. The question was always whether you believed him, and he always had been pretty convincing.

His answers were famously short, but not curt, rather upbeat. There were often awkward silences where it seemed normal for him to say more. Awkward for you, perhaps, but not Dylan, who never doubted for a moment that he had said enough, and was smiling in wait in case you had another question.

I met Dylan in 2017 in the bowels of the stadium for the Low-A Greensboro Grasshoppers, which were somehow darker and more dankly lit than "the bowels of a Low-A stadium" would already imply. I needed to also talk to Jake Burger, Micker Adolfo and Blake Rutherford that day, and Dylan -- an unrefined power arm seemingly oceans away from being relevant to the major league roster -- was last in line.

Cease, sweating profusely after a session in some broom closet of a workout room, was in a wildly different situation than he is now. The 2017 Kannapolis Intimidators -- whose own home locker room had a sort of two-shipping-containers-welded-together look -- had this weird little thing where they never won when Dylan pitched. He didn't even throw his signature slider back then, and unbelievably, we spent some of that interview discussing a two-seamer they had him working on. His short answers were counterbalanced by how honest they were. His changeup, by his estimation, was not good. His control was nowhere near where it needed to be. He was in Low-A, he figured, because he deserved to be, and substantial reps were necessary for him to improve.

And yet he was also the same as he is now. Most prospects are actively straining against their placement, insisting upon their readiness for more, but Cease had no problem admitting these faults. They were not his failings, but merely his to-do list. He just needed time, and seemed at peace with working and waiting. He usually is.

All the risks present in Cease's profile, all the dragons he had to slay to become a viable big league starter -- even when his fastball went out of whack for over a season, even when Lance Lynn had to grab him and tell him to stop thinking about mechanics on the mound -- were located outside a fence. Maybe 100 yards within that fence was a fortified concrete wall, and even if you scaled that wall there was a moat filled with voraciously hungry gators, and maybe another half mile within the boundary of that moat was a still-guarded compound where Cease's absolute confidence in himself resided.

The confidence Cease had in himself made me laugh a lot, which was perfectly fine since he was unflappable. I laughed when I showed him a painting I made at a paint-and-sip I was dragged to as a point of comparison to his own work, and he humorously indicated that he thought mine differed from his in that it sucked. I laughed when he gifted me a jar of honey from the hives his dad cultivated, unfazed by my protestation that a Cy Young candidate should not be providing goods or services to a Cy Young voter. "It's really good," was his position and he wanted me to try it, convinced these were the most important data points. He was right, it's perhaps the best honey I've ever tasted, and I still voted him second. I laughed when he confessed without concern, that the white pants he wore in his ridiculous video for his equally ridiculous slider poem, were ruined by his decision to drop to his knees in faux anguish in the mud. I always respect commitment to a bit.

I chuckled from the seats behind home plate as he eviscerated the High-A Astros affiliate in 2018. His reaction for all nine of his strikeouts over 7⅓ innings of one-run ball was this perturbed readjusting of his pants and belt, as if he was annoyed that he had to go through all this trouble. I laughed when he came out for the eighth inning and was still sitting 99 mph, astonishing the Dash fans around me and looking as indefatigable as the workhorses I grew up watching. I kind of laughed watching him walk around the White Sox clubhouse the last two years, assured and at ease with what he was doing, even as it all melted down around him.

There's a scenario, at least in the weirdness White Sox universe, where Cease's fastball cutting issues waylay his career as a starter for far past the 2020 season, and the heights he was able to reach on the South Side are never realized. That was acknowledged in his farewell message to the team and the city, in which Cease credited pitching coach Ethan Katz for "turning me into something usable." From the outside, much of his early years were spent with only a tenuous hold on the path his career has been able to follow.

Cease threw so hard as a sophomore that it filled his high school coach with amazement, but also quickly with terror that his body was not ready for the stress. By his senior year, those fears were realized and his elbow blew out. His twin brother Alec, in an interview Cease wasn't too flustered by his major league debut being that day to facilitate, revealed that a torn labrum had ended his time on the mound.

That history meant that we never witnessed a Cease who wasn't regimented and routine-oriented in his throwing program, bearing the hallmarks of someone who had undertaken a surgical rehab process before earning his high school diploma. It made him risky and less valuable in the 2014 draft, perhaps just another young arm who powered up and blew out before he learned how pitch. But Cease never seemed staggered by the notion that his body could fail him, just aware of it. It says something about Dylan that he hasn't missed a start due to arm pain in five seasons, and especially in light of his recent allusions to triceps issues in the past, it's not simply that he's been inordinately lucky.

Because obviously he has been pretty fortunate. He came up well from the Atlanta suburbs with enormous physical gifts, became a relative paragon of health despite high velocity and a major surgery early in his development, and stuck as a starter despite fringe control and not discovering his primary pitch until years into his professional career. His progression doesn't seem repeatable unless the lesson is that statistically some scratch-off tickets must turn into winners.

But Dylan never seemed to doubt it could be done, so much that it seems like a shame to not make greater use of when one of these guys comes along.