Sergio Santos only spent three years in the White Sox organization before returning this season as the manager of the Birmingham Barons, but he arrived in 2009 and departed in 2011 under circumstances so unusual that Santos described both with the same phrase:

It was kind of weird how it happened.

Santos was invited to White Sox spring training in 2009 as a position player, but the team saw a more promising future in relief. Santos wasn't ready to concede yet, so the White Sox traded him to the Giants in order to see his position-player future all the way through.

But there was a catch: If he wanted to explore pitching, the White Sox called dibs on the conversion. Sure enough, the Giants didn't have a Triple-A shortstop job for him, so they sent him back to the White Sox, and Santos said everybody held up their end of the bargain.

"It was just kind of, 'Your word is your bond. We'll get you there for a player to be named later,' and I think [the Giants] ended up sending me back for that same player to be named later, and that was me, right? So it was kind of weird how it happened, but grateful that it did happen."

After speeding his way through the minors in 2009 and successfully learning on the job in a major league bullpen in 2010, he pitched his way into the closer role with 30 saves in 2011. At the end of that season, the White Sox signed Santos to a three-year, $8.25 million contract with three club options.

But two months later, the White Sox traded him to the Blue Jays for Nestor Molina.

"I love Chicago, my family loves Chicago, so when I signed that three-year deal, we're all excited, like 'Hey, we're going to be here for the next three years, it's going to be great,'" Santos recalled.

"And I remember I was golfing with my neighbor in the offseason, and I was 2-over on the front and I was playing great, and then Kenny Williams gives me a call on the turn. When he told me I got traded, I said, "All right, just tell me it's a West Coast team,' and he said Toronto, and I was like, 'Oh my...'.

"I got traded to Toronto twice. I got traded to Toronto in '05, and it was me and Troy Glaus for Orlando Hudson and Miguel Batista. So it was kind of weird how it happened, but it's a business at the end of the day, and it happens."

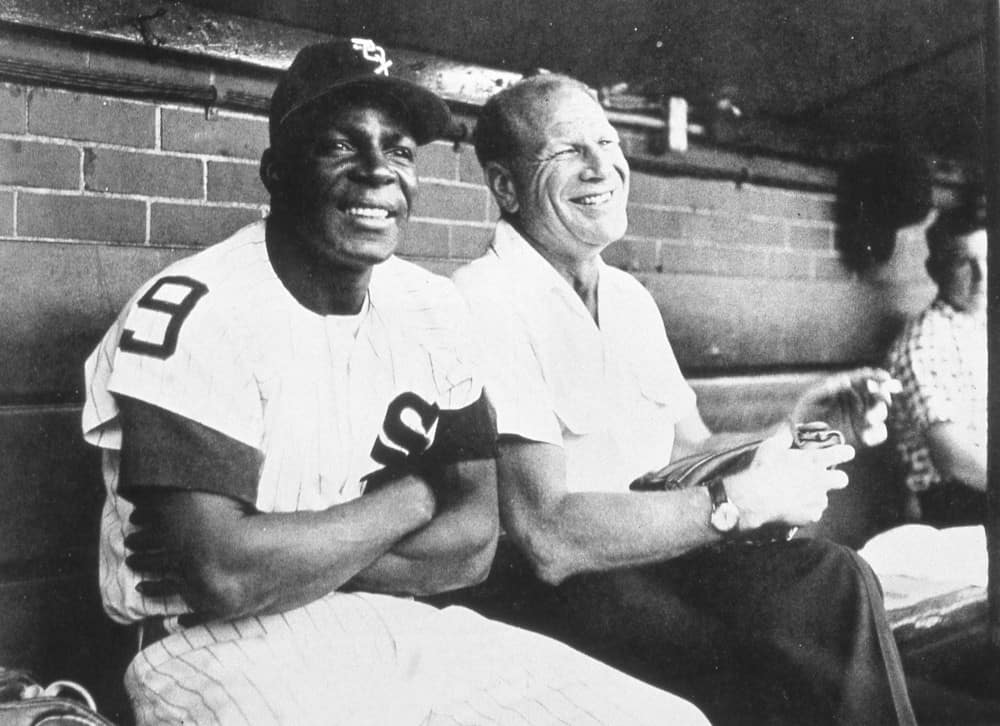

His entrance and exit as a player were among the numerous topics Santos and I talked about over a 12-minute conversation in the first-base dugout during the Barons' season-opening series. I'd previously shared Santos' insights with regards to minor league winning percentages and Brooks Baldwin, but here are a handful of other highlights from the transcript before the season creates new stories.

On becoming a manager

"For me, I was 4 years old and I said, 'I wanna be a Major League Baseball player,' and I was blessed and fortunate enough for that to happen. But when it's over and you're 35, it's, OK, what am I going to do for the next fifty years, right?

"So I started working for Major League Baseball at their youth academies, and they had five across the US. They're all kind of urban, tough areas and so California, mine's in Compton, and so I did that for almost three years. And it was so gratifying and just awesome to see these kids grow by just injecting positivity, belief in them and just kind of seeing how that happened.

"After that, I said, 'You know what? Maybe I'd like to get in player development,' and so the Yankees had reached out and said all they had was a managerial role. At first, I was a little hesitant. I didn't know if I wanted to be a manager, but the more I thought about it, it just made perfect sense with my uniqueness of my career, my background, and the way everything is, where, like, I'd never played for a manager that can relate to every single person in the dugout. I've been in every single one of their shoes, and I felt like that's a pretty good advantage over most managers.

"It's worked out. I love it. It's a dream come true."

On that uniqueness

"I've been that everyday player, every single day, to being a relief pitcher ... I feel like the guys know it. I can have a pitcher ask me a question, I can have an infielder, hitters ask me questions. Through 16 years of pro ball, there's a vast amount of experience that I do have, lessons of things I did the right way and things I did the wrong way, where if I can save them from making the same mistake, it's a win."

On climbing the ladder

"They say it's a small baseball world, and it really is. I mean, people jump from organization to organization, people I played with and played against, so it's a community, it's a family. And yeah, if your contract's coming up it's, you run into people, farm directors and different GMs and this and that, and you just stay in touch, and it becomes a conversation, and if there's something there, then that conversation goes further."

"It's not really a level for me. If I can't control it. I don't worry about it, and what I can control is what I do every single day. I tell the players this all the time: Be present, be where your feet are. And I feel like if I do my job and I do my job really well, that'll take care of itself; I'll move up and I'll get to where I want to be eventually. But I'm in Birmingham now, so I'm trying to be the best Double-A manager I can be."

On Drew Thorpe

"Thorpe was with me all last season, and he's one of the guys that I've ever been around that just has that 'it' factor when it comes to mound presence, when it comes to confidence. He's very quiet, soft-spoken off the field, but when he gets up there, he's just an animalistic competitor. My man just loves to compete. He attacks people. And what I love most about it is, even on a day that if he gave up five runs in the first inning, you would never know it by seeing him in the dugout. He can compartmentalize and get back out there and do his job.

"His changeup is incredible. It's one of those pitches that you can throw over and over and over again in a game, and somehow hitters still miss it."

"For me, when I was pitching, I was a fastball-slider guy. When it got to two strikes, everybody knew the slider was coming. I knew it, they knew it, but they still have to hit it at the end of the day. If you have a good pitch, you've got to do it.

"That's what I've tried to impress on the pitchers, where, coming as a hitter, it is incredibly hard to hit. It is so hard to hit. Sometimes as pitchers, they try to be too fine and nitpick, worried that they're going to get hit, where in reality, the more you attack the strike zone, the more outs you're going to get. Hitters are going to get themselves out."