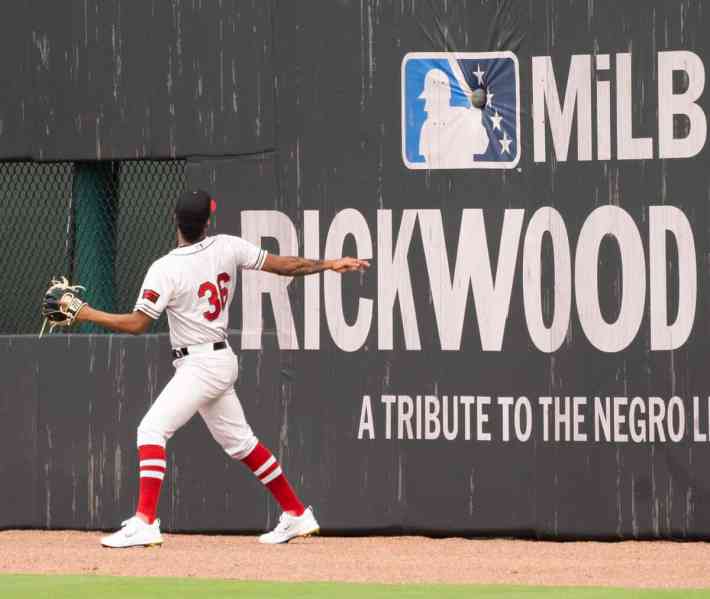

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. -- The time I'd spent actively considering Rickwood Field's outfield walls had been mainly devoted to the handsome manual scoreboard in left field and the outsized batter's eye in center, but I'm pretty sure that some part of my brain realized the fence wasn't wooden. The modern-day advertisers -- Mastercard, Gatorade, the suddenly ubiquitous buildsubmarines.com -- attempted to capture the feel of antique advertising, but the colors were a little bit too consistent, too muted, to pull it off.

But even though I probably knew the fence was padded everywhere besides the chain-link sections, I was still a little bit surprised when Jairo Iriarte flung a weighted ball at a panel in right center field as part of his pregame warm-up, and it didn't go clear through.

To walk around Rickwood Field is to fall into a real tug-of-war between what's real and what isn't. What's authentic and what's commercial. What's old and what's new. What isn't technically supposed to be there, and what has to be now.

Most of the time, the tension reveals itself in subtle ways, like wending your way out of the grandstand down some aggressively noncompliant concrete steps, ducking under support beams on the way out, and seeing a station for nursing mothers when you can straighten your neck. Or wondering about the stability and efficacy of the light banks leaning over foul territory on the first- and third-base sides, only to realize the larger mobile light stations behind them will be the ones in use.

But if you want to put it all out in the open, stand on the roof on the third base side. Turning to the field, you can see batting practice to a pregame soundtrack of Charles Mingus and Louis Jordan. Face away from the field, and you'll hear Flo Rida and Anita Baker coming from a massive soundstage, playing to a fairgrounds midway. The tents for merch and vendors give it the air of a carnival, and the sprawling tents for clubhouses suggest you're really walking around a movie set.

Which makes sense. Just like the Field of Dreams Game, MLB at Rickwood Field is going to look amazing on TV. You're going to see the old charm of flaking paint and rust from the steel-and-concrete grandstands, and it's going to stand in pleasing contrast to an impeccably manicured playing surface. Every MLB field is a Scott's devotee's dream, of course, but this one has been under construction for six months, and Tuesday's minor league game was the first time it saw game play, so there aren't even the less-green spots from where the outfielders typically stand. From the warning track, it looks like you could roll a baseball from one foul pole to the other. In previous iterations of the Rickwood Classic, any attempt to follow a rolling baseball risked rolling an ankle.

Everything necessary to staging such an event has to be hidden away, which is why you can't walk all the way around the field see the original concrete wall denoting Rickwood's previous dimensions.

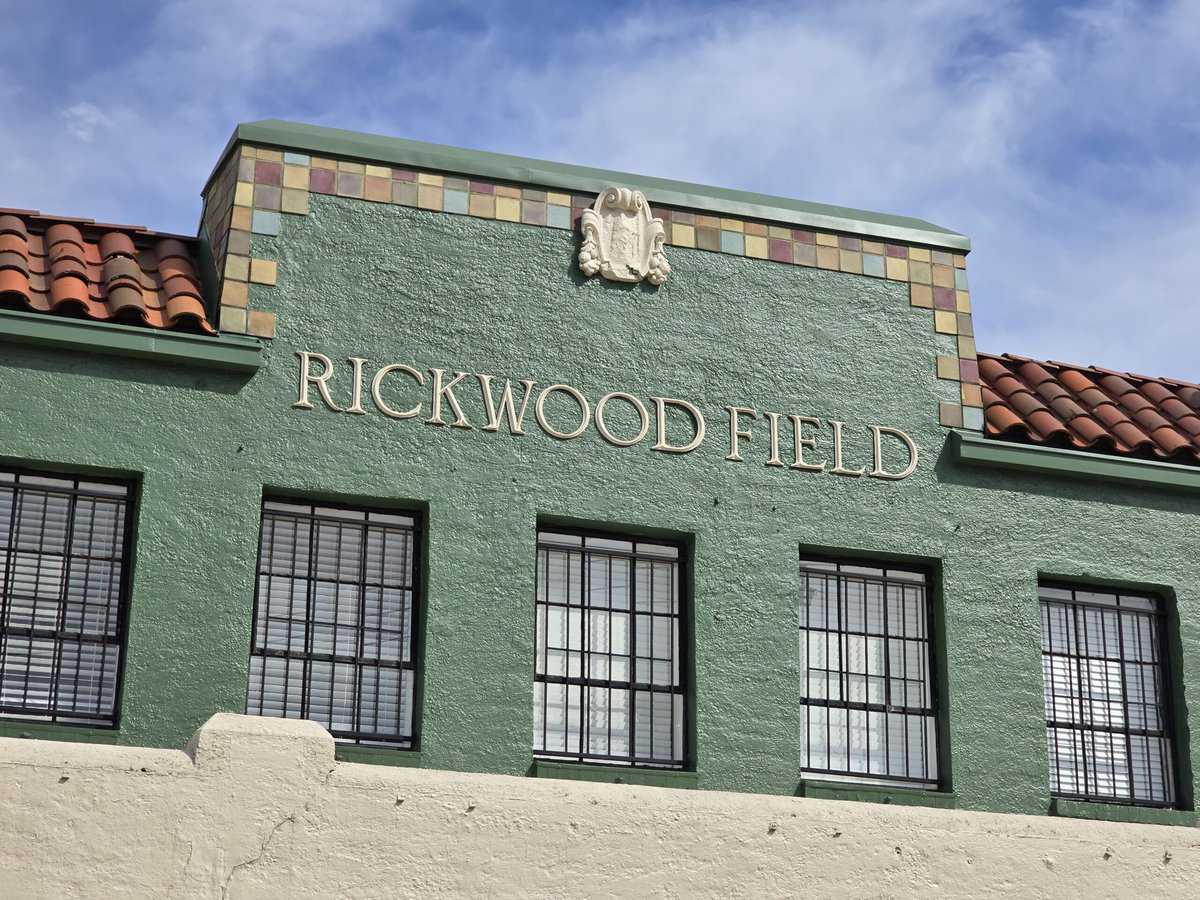

And due to modern-day standards for security and scrutiny, Rickwood's beautiful, restored main entrance is one in name only. By the time you encounter those turnstiles, you've already passed through a labyrinth of checkpoints for bag inspections, metal detectors and ticket scanners. There's no way to see the ballpark from the neighborhood right now. The only signs of a stadium from the street are the numerous barricades at every potential entry point, and the mobile light towers behind them.

All of those modern-day headaches can take you out of the experience of visiting a ballpark that predates Fenway and Wrigley, but once you're in the grandstand, you can easily lock yourself back in.

The news of Willie Mays' death broke at the end of the sixth inning, and it was announced over the ballpark public address system after the seventh. A video tribute followed.

Rickwood Field is where Mays got his professional start as a member of the Birmingham Black Barons. While there are ample reasons for Major League Baseball to honor the Negro Leagues with such a game, Mays is the biggest driving factor for Rickwood being the specific place for it, and the Giants being a team involved. It's a shame he won't be around to see it, but an incredible celebration of life service could provide a considerable consolation.

The fences might be different, the lighting might be different, the entertainment might be different, the advertisers might be different, but when you're sitting in the grandstand, looking up at the rafters and around the support beams, you're seeing the same field Mays manned as a teenager in 1948. Just don't make the rookie mistake of picturing him in center field, because he debuted in left.

There are only a handful of places like Rickwood in existence, which makes me wonder what's going to come of it when the circus leaves town. The perimeter of stagecraft and security effectively walls it off from the west side of Birmingham, and the conditions that led the Barons to vacate Rickwood decades ago -- first for suburban Hoover, and then back to downtown at Regions Field -- remain in place. Millions have been spent to make the ballpark a viable place to host a big-league game, but there's way more work involved in making the effects last.

I hope they have a plan. Sitting inside the ballpark gave me a sense of watching Mays, Jackie Robinson and Babe Ruth roll through town, but I'd like to revisit Rickwood to get a better understanding of the setting for it. I'd like to see the exterior, alternating stately and ramshackle, from the sidewalk, instead of in front of a temporary Chevy showroom next to an impressive Negro Leagues exhibit. The game has been designed to draw attention and awareness to Rickwood Field. Mission accomplished for me, and for hundreds of thousands on Thursday. Once that's banked, what are they going to do with it?