If you're familiar with White Sox crosschecker J.J. Lally, it's most likely recognizing his name as the signing scout for top pitching prospect Noah Schultz. Maybe an astute reader remembers him having the same role last July for towering power-hitting prospect George Wolkow out of Downers Grove, where Lally spoke to his goal to find and draft the next Aaron Judge, viewing it as the more likely solution than the team signing such a player on the open market.

Maybe a real Sox diehard remembers that Lally was trying this gambit a few years prior, when he sought to convince Bears tight end Cole Kmet to pick baseball over a scholarship to Notre Dame. Last month, I shadowed Lally on a day spent in the very nascent stages of this process.

The Big Ro Coleman Classic in Kenosha, Wisconsin is a four-day tournament of travel ball teams, featuring rising high school juniors and seniors. Whereas we had previously planned an outing where I would watch Lally track a single Midwestern prospect -- a likely second-rounder in this year's draft -- this was the opposite type of focus. At the end of nine hours in the sun, shuffling between four different active fields, Lally planned to make 15 entries in the Sox database. In many cases, like the man-sized rising junior we watched sit 90-91 mph for a couple innings at the end of the evening, it will be their first mention in Sox records; an initial sketch of his raw ingredients to prime follow-up looks.

Schultz and Wolkow both once played in this tournament -- Wolkow recently estimated he played over a dozen games on these fields -- and similar profiles would be the crown jewel of this mission. Teams will commit money to bring outlier physical tools into their developmental system. Players who distinguish themselves more with competency, skill, approach with average physical ability are better off raising their value by continuing to do it in college.

Area Codes

Scouts, and pretty much all team employees, hate the MLB draft being moved from early June to the All-Star break is well-known, and this event really lays it bare. While the most stressful week of the year -- the 2024 MLB draft -- is still bearing down on them, vital work for the 2025 Draft has begun. One scout seems charmed by the idea of me writing an article about their day-to-day work, since this is a time of year where it feels especially unconsidered. For Lally, it's worse. July 5 was his deadline for finalizing the White Sox roster for the 2024 Area Code Games, a six-day tournament showcasing high school prospects via regional All-Star teams.

Only eight MLB clubs take up the responsibility of handling a team, which leaves the Sox with a comically large task of building a team from a 17-state "Midwestern" region. Last year's team was uncommonly strong and will be well-represented in this year's draft, led by likely first-rounder Ryan Sloan from Elmhurst. Traditionally Midwestern kids are held back by cold weather reducing their opportunity to play, forcing evaluation even more guided by projection than 16- and 17-year-olds already require. Now that biomechanical analysis is part of the equation and delivery corrections that unlock another level of velocity and command are more common, scouts must be even more imaginative.

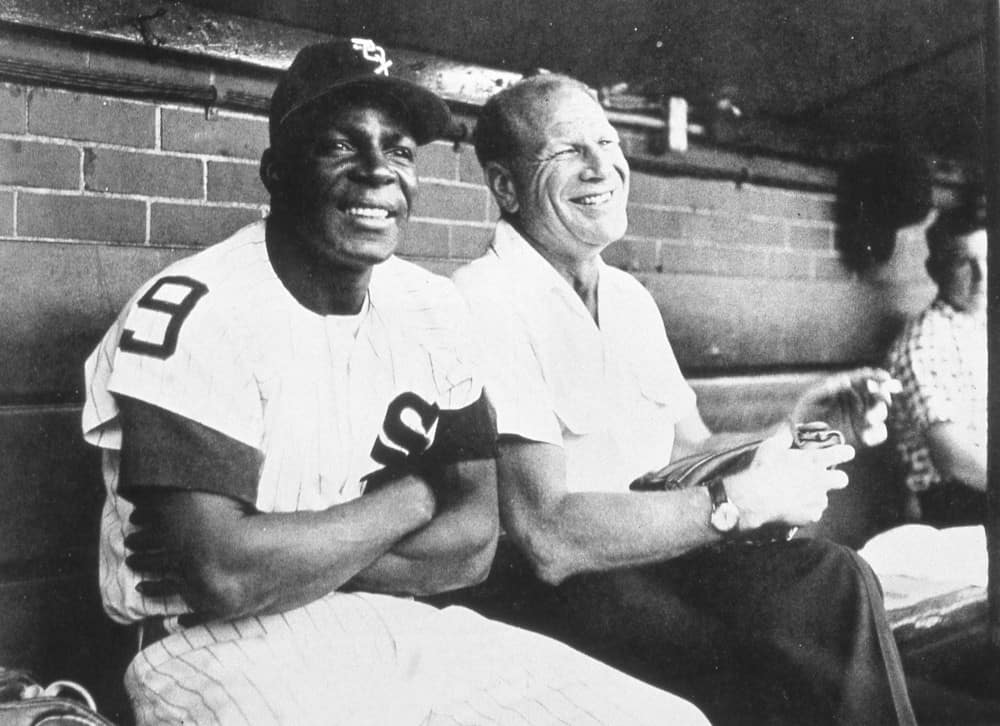

With 22 organizations abstaining, this might seem like an unnecessary to-do. But the sight of Lally stalking the tournament in a White Sox hat and a hoodie with "AREA CODES" emblazoned across his chest is just a hint of how much he views this practice as essential to his mission. On some workdays, scouts seek to go unnoticed, usually when honing in on a single player. When and how to deploy Jim Thome, who recently watched a prospect's game from the left field corner to avoid being spotted, is an amusing predicament for the White Sox amateur scouting department.

But on this day, Lally is planting a flag and holding court. Recently promoted from area scout, Lally is already wired to rue the idea of getting beat on any Midwestern talent, but his belief that the White Sox must draft-and-develop their way to success and should leverage their proximity to dominate this region of the country turns that mentality up to 11. Selecting the Area Codes roster, being visible at this tournament, and fortifying the notion that the White Sox are all over young talent in this part of the country, is all part of it.

The returns are easy enough to perceive. The players, disarmingly self-aware and professionalized even as young as 16, approach Lally and the small contingent of rival scouts he is sitting with and provide updates. This is where a heads-up about the Class of 2026 right-hander sitting in the 90s comes from. Some of the more novice players resemble Winter Meetings jobseekers -- knowing they should network, but not necessarily where the conversation should go -- but often they have a smooth and easy rapport with Lally and scouts they have become familiar with seeing. It's a marvel seeing how perceptive a young catcher is of his quality of competition and his place in it, but Lally is mindful of the strangeness of it all. "Have fun," he repeats at the end of every chat with a player, trying to give a reminder of the oft-forgotten original purpose of this tournament.

The high IQ player

A typical quandary of scouting high school players marks the first game we watch. The best player on the field is an undersized shortstop without remarkable tools. Lally likes him a great deal for reasons scouts tend to remember. He arrived to the field early with a regimented routine for getting himself ready, his on-field IQ is notable and he corrects his teammates' mistakes -- frequent at this level -- directly, but without scorn. Scouts touting great makeup is often dismissed as cliche, or lacking intrinsic on-field value, but I suggest that these are the sorts of qualities that raise a player like Brooks Baldwin from an average collection of tools to a versatile and dependable utility player, and Lally co-signs that interpretation.

Baldwin, however, was a third-day college senior sign, not drafted out of high school. Lally notes the irony that he spends so much time scouting high school players, but only a small handful of high school players are drafted by the Sox each year. More often, he is starting the process of following a player's trajectory and building a relationship. The star players that scouts get associated with usually are a fraction of their work. Because of my recent ACL trip, Lally spends part of our day asking me about the progress of Wisconsin native Christian Oppor. Lally scouted the slender lefty as a high school player for years, though his name will rarely be associated with Oppor after he was drafted out of a Florida junior college.

Every prep player drafted has to bought out of their college commitment, so allotting that budget pool room is a heavily considered organizational strategy, and is usually centered around undeniably bankable physical tools. This undersized shortstop will have to keep proving that his skill set works against every new level, and just as readily as Lally can laud his makeup, he can recount a story of a pitcher who committed innumerable faux pas but had grown far too talented to leave off the Area Codes roster.

While Lally takes it upon himself to inform players personally when they're late cuts from the Area Codes roster, and tries to find funding when families lack the funding to make the trip, this is his work, not his charity.

"It's not actually an All-Star team," Lally said, reiterating that the purpose is to showcase pro prospects to MLB scouts, not reward high school players he likes.

Feel for spin

There's a similar conflict on the pitching side of this game. A left-hander has two viable breaking balls that he seems pretty capable of locating at the bottom of the zone. He's not dominating, but it's a consistency that stands out at a level where, as Lally describes, seeing one out of every four offspeed pitches executed well is about typical. This is an age group where the scouting axiom of "if you see it once, you know it's in there somewhere" applies, and this rising senior is showing what looks like advanced feel for spin.

Later in the day we'll see a rising junior who could easily pass for being in junior high, but also lands his breaking ball as often as anyone we'll see this day. His physical projection is such a mystery that it's not clear what Lally will put in the system beyond his name, age, school and "can spin it," but just making sure nobody worth tracking slips through the cracks later on is today's real goal.

But the older left-hander is 6 feet tall and lacks the gangly look of so many players who are still growing or filling out. There are few impact major leaguers who have his current build. To boot, he has a commitment to a traditional power program in hand, and seems like he should flourish in college ball. He's one of the better players here, but Lally puts him on the bubble for Area Codes, as he's less likely to be relevant to the pro scouts in attendance.

A special bat

It can seem like a whole lot of body scouting is going on, and sure, that's true. When a bunch of 16- and 17 year-olds are playing, very few things are being done at a professional level, and physical dimensions are some of the rare elements that can resemble the game we watch on television. But that is broken up a little bit by a left-handed first baseman in the second game we watch.

"He certainly walks around like he can hit," one scout jokes.

This can sound like a quote from the scout characters who are derided in Moneyball. But for one, it's a joke, since this player is well-known enough for his hitting acumen that everyone present has seen him before and already has an idea of how good he is. But also, at the prep level, this kid does move around with more assurance than everyone else. He clearly has a rigid routine he follows in the on deck circle, where other players are more excitably fidgeting around. He never seems off balance even while taking or fouling off pitches, or even while having a fairly ordinary game at the plate.

I had been feeling pretty good when Lally and other scouts had been validating my body and projection assessments, but this is where the job starts feeling like a unique skill set that I might just not have.

"It just sounds different off his bat," one asserts.

"That's some real bat speed," said after a single swing viewed from behind a fence.

Still trying to apply all the projection lessons I picked up during the morning, I ask if there's not some concern that this appears to be a physically mature first baseman who stands 6 feet even.

"He's trying out the outfield," Lally assures.

I may not be a scout, but I can read the room. And the professionals around me have identified a potential plus hit/plus power combination, and those are both rare at this level, and rare in this class. Lally feels the dearth of hitters is a cyclical thing rather than some generational failing, but the main point is that positional concerns for special bats is something that gets fretted over further along in the process than the Big Ro Coleman Classic. Here, Lally and others are trying to affirm who should be followed over the upcoming high school season, and this is a bat to watch.

Honor among scouts

Lally is watching most of these games with 2-3 scouts from other teams near us, sharing small observations aloud and verifying that everyone is seeing similar things. It's not dissimilar from how reporters operate, but it might surprise a newbie to see these competitors operating somewhat as a collective. There are secret missions in this job, and I've interviewed Lally and listened to him beam about scouting Schultz at a summer prospect league when other teams had dropped off the trail.

But like beat writers, scouts who cover areas, regions, wind up seeing their competition at games more often than they see teammates. Especially with the turnover and shrinking of the industry, camaraderie forms, and shows up in little moments. A fellow scout gets talked out of an hours-long drive to see a player who can launch long home runs, but does so via cartoonish hacks that seem unlikely to play against college velocity, let alone professional. Nights with family are rare commodities, and he shouldn't waste one on a "caveman swing." Another scout walks up and asks if he's at the correct field to see the huge right-hander who sits in the 90s, and no one steers him wrong. That would be strange, and this job is all about relationships, trust, and feel.

The complete package

We've been watching all these games alongside a scout who has been in the industry 50 years. He's drafted a Hall of Famer, has the prototypical demeanor and humor of a weathered Baseball Man, but also works for a famously progressive organization that views him as too essential to allow to retire. A tall and lanky rising junior shortstop (who also apparently can hit 92 mph off the mound) walks up to him and says hello. He will prove to be the most electrifying player we see all day, but is already familiar with the veteran scout who first saw him play weeks earlier than everyone else. It's almost like some of these old, experienced guys know a thing or two.

"What did you say your 60 time was again?" the scout says, asking for a 60-yard dash time.

"6.6," the player says with a easy smile. They usually know what measurables scouts are keyed in on, and can reel them off readily. If I ever knew my 60-yard dash time at age 16, I quickly strove to forget it.

On the field, the prospect looks at least 6-foot-3 but likely still growing. He flicks the ball across the diamond from short without coiling his body to do so, and Lally throws out that it might already be a 55-grade arm now, without even accounting for more physical maturation. The veteran scout tells me to watch his footwork; a light patter on the dirt that allows for easy change of direction. He's a combination of all the elements we've been looking for all day.

I break my drought of saying anything smart by pointing out that he's Colson Montgomery-sized -- including the part where he seems like he could easily also be 6-foot-5, 230 pounds in a few years. Proto-Colson moves with a loose assurance in pre-game warmups. He makes routine plays look routine at short, at a level where every grounder to the left side offers some potential for chaos. His first at-bat, a lineout to short, generates "oohs" at his bat speed that I assume is well-founded. It would nice to see a high school player I'm supposed to get excited about launch three home runs in a game and make everything unambiguous. But this player comes up with the bases loaded his next time up, and the only strikes he sees are away, away, away, so he calmly sprays a line-drive to the opposite gap for a two-run single.

"Look at the way he stayed inside that ball," Lally said. "I'm getting tingles."

There's a report to be written up when he gets back to his hotel room. He's staying overnight because there's a player he needs to see in an 8 a.m. game the next day. For now, his approval is marked only by taking out the team roster, and underlining the player's name. This is a long, multi-faceted process that is unlikely to end with this player donning a White Sox uniform. Even if it does, it will probably end with someone else explaining the investment.

But on this day, Lally played his part.