The White Sox are in unprecedented territory, at least in franchise history. They're showing all signs of standing alone in putridity at the end of the season, too, but like a Ford F-750 in Maine, we'll crash through that quaint covered bridge due to a hilariously egregious violation of the weight limit when we get to it.

It's bad enough that these White Sox managed to discover uncharted territory for a franchise that's not known for success with their 107th loss on Sunday. What's worse: The only team that lost as much as they did wasn't remotely comparable before they were left behind, mainly because they were already doing something about it.

Sure, the 1970 White Sox were terrible, which their 56-106 record and total attendance of 495,355 explains well enough. They coupled a below-average offense with a league-worst pitching staff that couldn't quite figure out how to transition out of their excellent run in the mid-1960s. Even then, they were an ordinary kind of lousy. They stood a chance of losing fewer than 100 games until a 7-20 finish to the season pushed them over the edge.

Softening the blow, the results of the September games were largely besides the point, because owner John Allyn had committed to sweeping changes at the start of the final month. He opened September by firing executive vice president Leo Breen and general manager Ed Short. He started the replacement process by installing Stuart Holcomb, the White Sox promotion director who coached Purdue football for 11 years. The next day, Holcomb fired manager Bob Gutteridge, replacing him with Jerry Adair on an interim basis.

Just like the firing of Pedro Grifol, that wasn't enough to reverse course. The White Sox opened September with an eight-game losing streak, including three walk-offs over the span of four games, and they closed the year with seven losses in a row. Over the last homestand, they topped out at 3,826 fans, and bottomed out at 642.

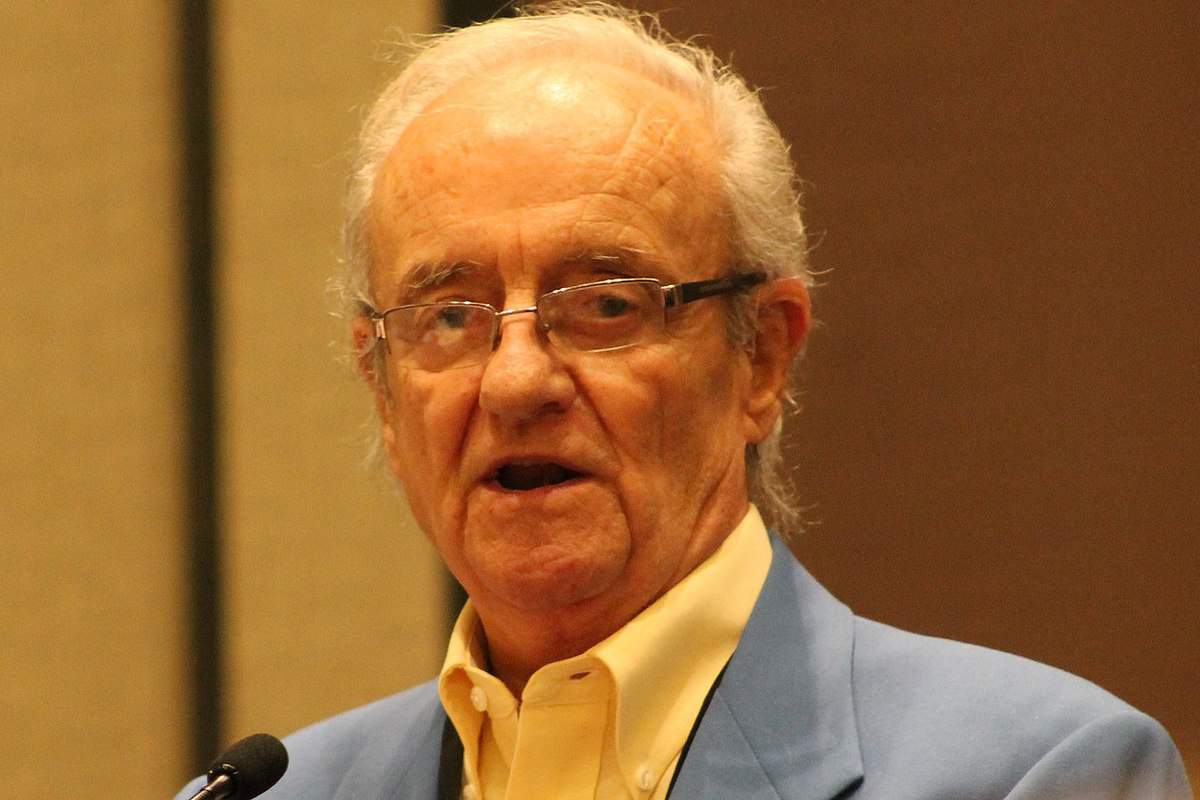

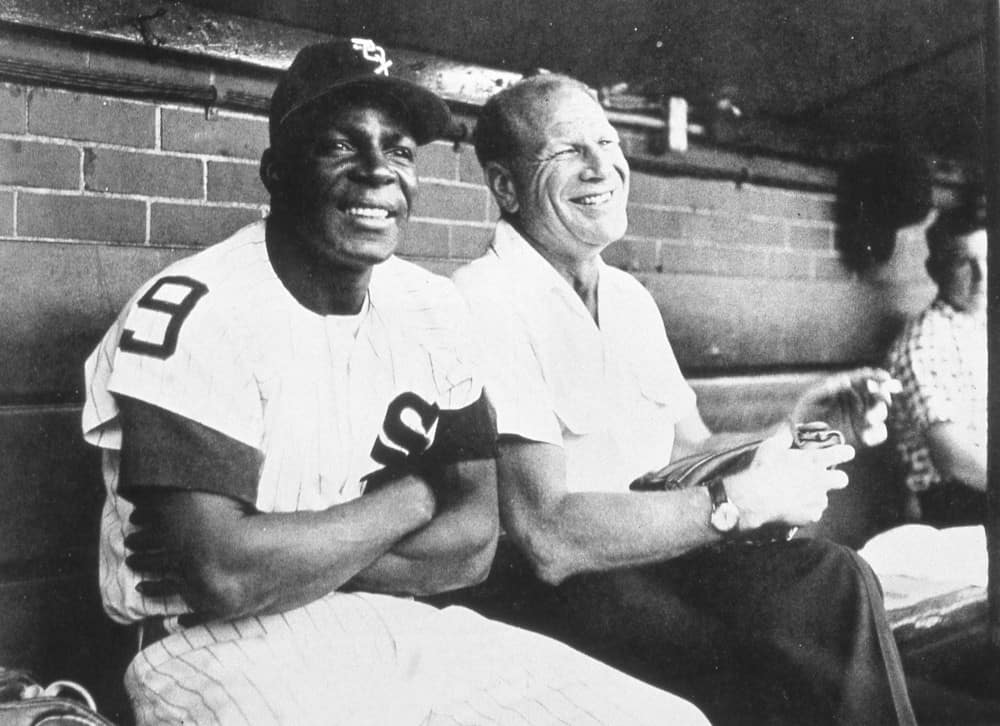

Yet the organization provided plenty of other distractions. They actually hired their director of player personnel and their new manager during the final month, and both came from outside the organization. Roland Hemond and Chuck Tanner were both plucked from the California Angels on Sept. 4, and they both reported to work on Sept. 15, although Tanner didn't make his official managerial debut until Sept. 18 due to rainouts. Joining them was new pitching coach Johnny Sain, also hired from the Angels system.

They were formally introduced to the Chicago media on Sept. 14. The Chicago Tribune's story introduces another key difference in rhetoric:

Owner John Allyn was also present at the meeting. In his brief introductory statement, he said, "The credit is due to these men if we succeed. If we fail, it's my fault."

On the field, White Sox fans could at least follow Bill Melton's pursuit of the franchise's single-season home run record. He entered September with 26 homers, three short of the mark shared by Gus Zernial and Eddie Robinson in 1950 and 1951, respectively. He hit two against the Angels on Sept. 9, tied the record in Tanner's debut on Sept. 18, and then broke it with a go-ahead solo shot off Kansas City's Aurelio Monteagudo three days later. Though it was only the 177th 30-homer season in the history of the American League, it was the first for a White Sox.

He hit it in front of the smallest crowd of the year to date, as only 672 fans were there to celebrate Tanner's first managerial victory.

Tanner lost far more than he won to close out the calendar -- he finished his debut season 3-13 -- but that was the only thing that stuck to the new guard in their first month. The real work wouldn't start until the season ended, and that's when Hemond began putting his mark on the team. Among a whole host of changes, he turned over three of the four up-the-middle positions, traded for a legit No. 2 starter, moved his closer to the rotation and a starter to closer. They improved by 23 wins from 1970 to 1971, and were an over-.500 club from mid-June through the end of the season, which gave Hemond the confidence to engineer the most important trade of his career, dealing Tommy John to the Dodgers for Dick Allen the following winter.

Going into greater specifics about Hemond's transactions would inadvertently minimize the ways a GM's job has evolved from 1970 to 2023. He didn't have much money to spend, but he also didn't inherit untradeable contracts to wait out because free agency wouldn't exist for a few more years.

Still, it emphasizes what makes the 2024 White Sox especially bleak. Not only are they a standard deviation worse than what Sox fans have ever seen, but they couldn't have squandered the goodwill from firing Kenny Williams and Rick Hahn any faster. Jerry Reinsdorf validated all concerns about his stewardship when he handed the team to Chris Getz without a search due to exceptional delusion or exceptional laziness, and Getz has validated all the concerns about hiring internally from an organization already in steep decline. I'm sure Getz had great ideas about what he could do better than Hahn and Williams, just like Pedro Grifol saw massive inefficiencies in the way Mike Matheny ran things in Kansas City. In the end, Grifol couldn't shake the notion that even one of the league's worst teams saw him as expendable. With Getz, Reinsdorf made the opposite decision from the opposite side of the table, adhering to the internal candidate no matter how little he'd accomplished. The result looks just as uninspired as you could imagine and then some.

The one element we can't account for is the financial component. Perhaps getting clear of the Yoán Moncada and Eloy Jiménez still frees up Getz for a greater roster overhaul, and he'll find reason to be more transactional even with less money to spend. He had to stick with Grifol longer than he cared to, and that would explain the half-measures and the repeating of bad ideas elsewhere. The sweeping sea change truly reflective of new leadership just might be delayed by a year.

But that requires a benefit of the doubt nobody in the White Sox front office has come close to earning. If you take Reinsdorf at his word -- and people like Steve Stone will tell you it means something -- he saw hiring Getz as the fastest way to get better, and instead they've gone from embarrassingly dysfunctional to historically inept, and there's no draft-day payoff to show for it this time around.

It reminds me of a John Mulaney bit about his terrible driving, saying that after abandoning a U-turn in preposterous fashion, "Cars were pulling up and looking over to see who just did that piece-of-shit move, expecting to see, like, a 100-year-old blind dog who's texting while driving and drinking a smoothie. Instead they see a 28-year-old healthy man trying his best."

If Reinsdorf actually meant what he said, my guess is that Getz humored his boss to get the job, but that doesn't stop the real-world ramifications from being so unbelievably grim. Getz got to fire a manager who exhausted the limits of "fake it 'til you make it" because he never got past Step One, but there's no way to rule out that Getz is doing the same thing, because this is exactly what it would look like. Until you see some proof that he's licensed to operate heavy machinery, everybody seeing this team on the road should take a defensive approach to driving behind, around or past it.