A couple of years ago, I reviewed “Hawk,” Ken Harrelson’s 1969 autobiography after finding a copy at a used bookstore in Cooperstown. As one might expect from a book written by a 27-year-old athlete, it's an exercise in hubris, and it's doubtful Harrelson even read it.

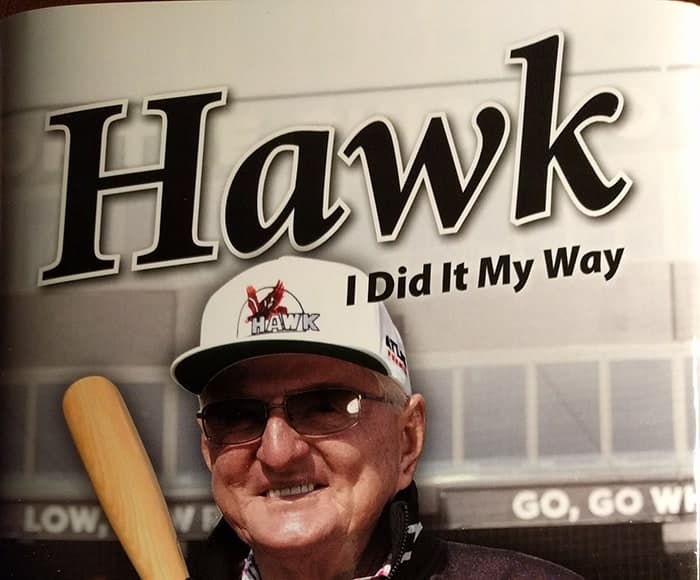

Nearly 50 years later, Harrelson has another autobiography with the same name, but with a few key differences. The full title is “Hawk: I Did It My Way,” the co-writer is Jeff Snook, and this time he has a whole lot more of a life’s story to tell. Harrelson no longer needs separate chapters about Frank Howard’s eating habits or his dry-cleaning bill to fill out 244 pages. Instead, he carries 377 pages mostly by himself.

Regardless, the result is the same: If you have a desire to read it, you'll find things to enjoy about it, especially if you can suspend your disbelief for a couple of evenings. If you're Hawk-averse, it won't make you warm up to him. In either event, this version should be much easier to find, as it's published by Chicago-based Triumph Books.

* * *

Thus concludes the two-sentence review. If you don't care about spoilers continue reading...

* * *

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]here is overlap with the 1969 book, in that the first 160 pages or so covers the same years of his life. Yes, there are still plenty of Hondo stories, but he also delves more into his one-parent upbringing and the numerous fistfights along the way, including one as a 9-year-old he still regrets.

He also covers his years playing winter ball in Venezuelan, although this chapter title (Hot Days and Wild Nights in Winter Ball) pales in comparison to the one in his first book (Caracas Capers).

As his celebrity grows, sections of the book turn into a firebombing of name-drops, including some turns as Tragic Zelig in the late 1960s. The way he tells it, Robert F. Kennedy says Harrelson inspired his hairstyle, Rocky Marciano wanted to set up a fight between Harrelson and Sonny Liston. Both Kennedy and Marciano died not long after. Frank Sinatra makes a couple of notable appearances, along with John Wayne, Robert Mitchum and many, many, many, many, many, many, many others.

Some of these stories are entertaining and/or enlightening, and some of them are tedious. For the former, I’m glad Harrelson established his origin as a broadcaster, both for the Red Sox in the 1970s and the White Sox starting in the 1980s. The best chapter in the book is about his relationship with Don Drysdale, as it's a pairing that I only know from YouTube clips, and he conveys Drysdale in a three-dimensional sense that makes it easy to understand Harrelson's sky-high regard all these years after Drysdale's death.

He also offers a spirited if incomplete defense of his one year as a general manager, ending with:

I believe I did a good job. I made some good trades, getting rid of some dead wood. I will go to my grave with my head held high.

As for the latter, there are two whole chapters devoted to golf. I can see one being warranted, because he quit baseball to try his hand at turning pro. It's a big part of his story. Tom Weiskopf, Fuzzy Zoeller, Greg Norman, Tom Watson, Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus and Ben Hogan all show up, not to mention all the celebrities in his groupings.

Golf or otherwise, the problem with accounts of Harrelson’s life – and this is at least the third one when including the MLB Network special – is that there’s never a second source that contextualizes Hawk, validating or contesting his stories. We always have to take him at his word, which would be easier if he didn’t undermine several of his own assertions in the book.

For instance, he laments the idea that teammates aren’t as close as they used to be, saying players need “15 or 20 limos, and they probably are headed in 15 or 20 different directions.” Ten pages later, he says, “Steve Stone has been my broadcast partner for more than nine seasons and I have never had lunch or dinner with him. And anybody who knows me knows I don’t even eat breakfast.”

He goes out of his way to take swipes at Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton (the latter is a total non sequitur attributed to an unnamed Air Force One employee). He also adds that Mike Ditka “would have grabbed [Colin Kaepernick] and made him stand at attention.” It's his book and he can sling mud if he wants to, but he then later bemoans “how divided our country is these days."

And when Harrelson introduces Jerry Reinsdorf – the subject of pages of praise here and there over the rest of the book – the paragraph negates itself:

The White Sox were in shambles and there was nothing in the minor league system, but Jerry improved everything. Chicago was really a White Sox town at the time. I think the Cubs were drawing a few thousand per game.

Harrelson doesn't sound enamored with Bill Veeck, and I generally agree that his tenure was untenable in so many ways despite his charm. However, if the second and third sentence are correct, then Reinsdorf's way of "improving everything" still resulted in the Sox squandering their market share over the course of the 1980s.

I wouldn’t expect Harrelson to feel different about Reinsdorf, because he's far from the only employee to love working for the man and benefit from the owner's extreme loyalty. But Harrelson's urge to create a monument leads him to curious interpretations of events:

Many in the media blamed Jerry for the players' strike in 1994, but all the blame should have been placed on Donald Fehr. It took a lot of strategic planning to get the game back to where it is today, and Jerry was right in the middle of it. He worked in tandem with Bud Selig, who became commissioner in 1998, to regain baseball's popularity for the fans.

Especially since later in the book, he says:

I have no doubt that long-term use of the juice isn't good for the human body, but when fans or the media ask me how I feel about steroids in baseball, I have one simple answer:

"The home run race saved baseball."

Hawk is his own unreliable narrator, and these excerpts are characteristic of the lack of introspection that hampers his endeavors. Even that's kind of ironic, as Harrelson described himself as a voracious reader of the self-help genre, "always searching for the so-called golden egg of a book that would help me understand my feelings, my mind, and my approach to life."

Some of the book’s limitations may be born from Harrelson’s reluctance to expose his family. He frequently cites the feelings of his wife and children for decisions he made over the course of his career, and so it’s not surprising that he wouldn’t air anything that could be construed as dirty laundry. (He didn’t even mention his first marriage, which is probably for the better, as there didn't seem to be a lot of warmth between them in the 1969 autobiography.)

But occasionally he’ll reveal something fascinating about his personal life that isn’t given the proper exploration or weight. After a few off-hand references to his sister, he finally sums up her life 269 pages in while talking about his reason for quitting smoking:

“My sister was a heavy smoker who had died of lung cancer when she was only 40. I was so proud of what Iris had done with her life after such a tough start, having to get married at the age of 14. She wrote a few books and became a gourmet cook. She also learned to speak fluent German, Russian, and Spanish. She lectured at Duke University and at the University of Toronto. She became an accomplished pianist. She also dabbled in acting and landed a few holes on stage in New York. And she was an interior designer, having turned my penthouse pad into a beautiful home.

“But we had a falling out several years before she died when I turned down her request to borrow $250,000. She had wanted to open a nightclub in downtown Savannah and I didn’t have that much cash at the time. Plus, I didn’t think her business idea was a good one. When I refused her request, she walked out the door and I never saw her again.

“Apparently, she never quit smoking.”

If this is true, then his broken household produced two highly accomplished individuals, and yet he dedicated more time to naming professional and amateur golfers with whom he crossed paths and from whom he won money. He similarly glosses over the tumultuous shift from Tom Paciorek to Darrin Jackson to Steve Stone, although he did cap off the Jay Mariotti story with a satisfying mic drop.

Despite the shortcomings, there are enough surprises in Hawk, as well as a boatload of superlatives, that make me glad I read it, even if it turned out to be as one-sided as the Hawk genre of literature and film usually is. I knocked it out on a couple flights over the weekend, with only the golf sections dragging. Apropos of nothing, Jim Leyland and Don Zimmer were the best third-base coaches he ever saw. Apropos of nothing is the best mindset to take into the book.