It feels like pitching strategy in the major leagues is evolving, or at least the approach in preventing runs is open to new ideas. We saw "The Opener" technique in Tampa work well for a Rays team that won 90 games in 2018. There has been a significant uptick in bullpen usage this season that might be partly because of weak starting pitching, or managers are trying to limit the damages of TTOP. Pitchers are combating launch angle and exit velocity by making adjustments to their pitches changing axis planes and increasing spin rate.

How teams went about keeping their opponents off the bases is much different in 2018 than it was in 2014. That's why in this second part of identifying the gaps between what postseason teams do well, and what the current White Sox don't, isn't just pointing out the differences but also finding the trends. Instead of pitching "better," the White Sox might have to throw differently than they have.

Previously covering the gaps in offensive production between the Chicago White Sox this season and postseason teams, this exercise is identifying areas in run prevention that need improvement. Consider this a warning; if you thought the difference in postseason teams offensive production to the White Sox was ugly, it's probably best to skip over the table below.

| Avg. Playoff Team | 2018 White Sox | |

| RA/G | 4.01 | 5.23 |

| ERA | 3.72 | 4.84 |

| ERA+ | 111 | 87 |

| FIP | 3.85 | 4.73 |

| WHIP | 1.26 | 1.43 |

| SO/W | 2.70 | 1.93 |

It's easy to point out all of the White Sox pitching flaws from this season. Starters, no team since 2008 has made the postseason with a sub 2.0 SO/W rate. Both the 2008 Philadelphia Phillies and 2009 Anaheim Angels made the postseason carrying a 2.03 SO/W rate. All the 2018 White Sox need to hit that mark was strike out 67 more batters or reduce the number of walks by 33. Nothing outrageous would need to happen to meet the minimum, but hitting the ten-year postseason average would look drastic. If the total strikeouts remain the same at 1,259, then the walks would need to reduce their total by 187 walks to 466 on the season. Or, if the White Sox wild command continued and the 653 walks remained the same, they would need to find an additional 504 strikeouts.

Dramatic improvement in cutting down on the walks will help the team FIP which has a similar impact on runs allowed as OBP has on a team's runs scored total.

Another major contributor is home runs allowed. Let's start by comparing the ten-year average which is 157 allowed. The 2018 White Sox allowed 196 home runs which are a number that's eye-opening until you compare to the recent trend. This season, the five American League postseason teams combined to allow 889 home runs or 177.8 per ball club. A bit of a drop compared to 2017 when the five postseason teams allowed 966 home runs or 193.2 per ball club.

The American League Central champion Cleveland Indians allowed more home runs than the White Sox with 200. Key differences are the Indians struck out 285 more batters and walked 246 fewer batters for a 3.79 SO/W ratio that fueled a team FIP of 3.79. Home runs don't hurt as bad when there are not many runners on base. Cleveland had a team WHIP of 1.21 which is below the ten-year postseason teams average of 1.26. Much lower than the 2018 White Sox team WHIP of 1.43.

As long as hitters continue to swing for the fences finding ways to get more loft in their contact plus maximizing exit velocity, I predict the recent trend of home runs allowed will continue to be higher than 170 in a season. Postseason teams are combating this by keeping those home runs the solo variety by avoiding walking hitters. If the White Sox had allowed the same amount of walks as the Indians pitchers, the team WHIP would reduce from 1.43 to 1.26, right at the postseason teams average.

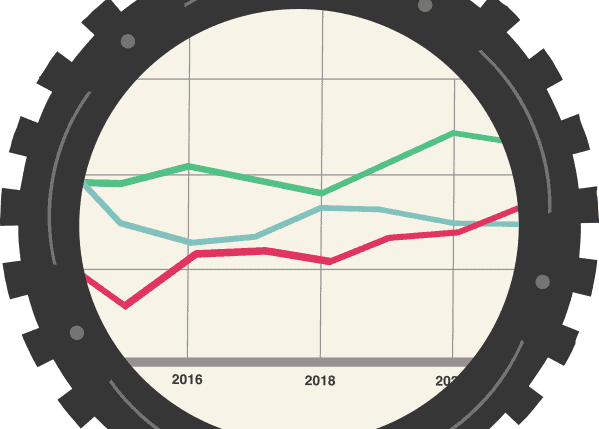

The White Sox have to find a way to reduce significantly the number of runs allowed before being considered a contender. In the table above, the ten-year average has been 4.01, but there is a noticeable difference between the two leagues over that time span.

| Season | American League (RA) | National League (RA) |

| 2008 | 4.30 | 4.16 |

| 2009 | 4.65 | 4.13 |

| 2010 | 4.17 | 3.92 |

| 2011 | 4.11 | 3.89 |

| 2012 | 4.15 | 3.80 |

| 2013 | 3.96 | 3.57 |

| 2014 | 3.86 | 3.73 |

| 2015 | 4.15 | 3.62 |

| 2016 | 4.33 | 3.77 |

| 2017 | 4.17 | 4.15 |

| 2018 | 3.92 | 4.07 |

National League teams should have the advantage in runs allowed because of not having the designated hitter. Interesting enough the American League postseason teams have fared better this season than their NL counterparts for the first time in ten years. The White Sox were close in 2015 and 2016 to the postseason team average thanks to a starting rotation with Chris Sale and Jose Quintana, but since their departure, it's been a predictable struggle.

When you break down the runs allowed per game to runs allowed per inning it's pretty easy to highlight when the issues start for the White Sox.

| Inning | White Sox | MLB AVG |

| 1 | 0.73 | 0.55 |

| 2 | 0.62 | 0.44 |

| 3 | 0.62 | 0.48 |

| 4 | 0.59 | 0.52 |

| 5 | 0.61 | 0.51 |

| 6 | 0.43 | 0.52 |

| 7 | 0.48 | 0.5 |

| 8 | 0.72 | 0.5 |

| 9 | 0.4 | 0.45 |

The first inning across the league has been the highest scored for quite some time. Jacob Peterson wrote about this very topic in 2011 for Beyond the Box Score. Starting pitchers are not in rhythm, and they are facing a team's best hitters right away. That's why I think there is something to the Rays opener idea, but there is a need for more data to confirm. Does a team give itself a better chance of winning if they use a pitcher they typically do in the sixth inning to start the first inning? Meanwhile, the intended starting pitcher continues to warm up in the bullpen to prepare to carry the second through sixth innings.

It's unorthodox and a bit unsettling for those that don't like change. What we do know is that bullpen usage is up in the majors, and it's been a significant upward trend for the last two years.

The White Sox have followed suit with the increase in bullpen usage as manager Rick Renteria loves to use multiple pitchers in an inning, but what postseason teams have is a dominant pitcher out of the bullpen who can handle multiple innings per appearance. Think Andrew Miller of the Indians or Josh Hader for the Milwaukee Brewers. This new bullpen role has been discussed with the White Sox as a role that former first-round picks Carson Fulmer or Dylan Covey can handle. Pitchers who struggle to face a lineup multiple times but can handle two to three innings without much worry.

Which leads to an open thought: would teams be better off having four pitchers who are effective for two to three innings than the old school model of using one pitcher to handle six to seven innings, and then the specialists handling specific batters? This usage is the method teams in the postseason use as it's becoming more common to see a starter get pulled by the third inning. Could a team find 12 to 13 pitchers and implement this strategy throughout 162 games? Would having them be prepared to take the ball every third day instead of the fifth day allow them to throw harder?

I ask these questions because the White Sox have many intriguing arms in the system to put this strategy into action. No expectations of it happening as long as pitching coach Don Cooper is around, but in the upcoming season if these young pitchers are still struggling going deep into games, maybe it's worth a shot. After all, the White Sox bullpen in 2018 performed better than the starters.

| Team | IP | K/9 | BB/9 | HR/9 | BABIP | LOB% | GB% | HR/FB | ERA | FIP | xFIP |

| Starters | 891.2 | 6.85 | 4.04 | 1.38 | 0.272 | 68.40% | 40.10% | 12.30% | 5.07 | 5.18 | 5.24 |

| Bullpen | 545.1 | 9.57 | 4.18 | 0.97 | 0.326 | 70.80% | 42.00% | 10.50% | 4.51 | 3.99 | 4.28 |

If the struggles for young pitchers like Lucas Giolito and injuries continue to critical arms in 2019, I'm not sure how the White Sox improve enough to make the transition from rebuilder to a contender. Either new faces would have to come via free agency or by trade, or a change in usage strategy. They need to find ways to cut their runs allowed because the offense is not going to be able to carry a mediocre pitching staff.

That run differential target Rick Hahn should be aiming for in his roster creation is +0.70 per game. That's the ten-year rolling average for teams that make the postseason.

Unless we see radical progress from Giolito, and the young arms prove to have sustainable success in the majors, what was once thought as a potential future strength could be a thorn in the White Sox neck.