With Madison Bumgarner becoming the latest name off the free agent board, the Sox are left with distressingly few options to address the gaping holes in their starting rotation. So perhaps it's not surprising that they've been tied to the Red Sox's David Price. Boston is looking to dump salary, and Price is the biggest one they've got, so it shouldn't take a huge package to get him.

And on the surface Price looks like a fit for a few reasons: former Cy Young winner, relatively short contract, and, perhaps most importantly, he can't say no to the White Sox. However, judging on the slightly more subtle "Is He A Good Pitcher?" scale, there are question marks. Price hasn't been a bona fide ace since 2015, and he's been largely ineffective and injury-prone the last three seasons -- part of the reason Boston is eager to dump him in the first place.

That said, he'd almost certainly be an upgrade over Dylan Covey, who is somehow STILL in line to open 2020 as the Sox's fifth starter. Price is also likely a better bet than the dregs of the free agent market -- your Homer Baileys and Ivan Novas. But with Hyun-Jin Ryu and Dallas Keuchel, both younger and better than Price, still freely available, at what point does Price actually make sense as an acquisition? And what's a package worth giving up?

To find out, I turned to a surplus value calculator created by the bloggers at DRays Bay, as well as a couple of tools from FanGraphs and Baseball Prospectus. I can see a Price deal structured in three different basic ways, and here's how the Sox can make sure that each would be worth their while.

Deal #1: Pure salary dump

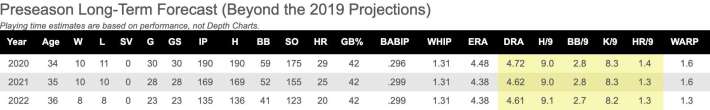

There's no denying that Price's deal is pretty far underwater. He'll make $32 million/year from 2020-2022, a total of $96 million. And here's how Baseball Prospectus projects him to perform over those three seasons:

Using the aforementioned calculator and a valuation of $11 million per win, Price's surplus value is around negative $42 million. In other words, Price projects to be worth a bit more than half of his future salary, meaning the Red Sox would have to kick in an offsetting amount for Price to be worth acquiring for literally nothing.

In that kind of deal the would Sox pay Price $18 million per year, and send Boston a non-prospect or two in order to do so (we're talking guys off the top-30, maybe in the vein of Joel Booker or Spencer Adams).

Deal #2: The Red Sox want to save more

If it sounds like Boston isn't saving all that much money in that deal... well, you're right. I'd imagine that as much as they don't want to pay Price $32 million to pitch for them, they also don't want to pay Price $14 million to not pitch for them. So in order to save more money, they'd have to kick in more value... and here's where things get interesting for White Sox fans.

Assuming that the new Boston front office has a couple untouchables (Rafael Devers, Xander Bogaerts) and a few undesirables (Chris Sale, Nathan Eovaldi), here are the Red Sox who might fit well on the White Sox, along with their approximate surplus value (again using Baseball Prospectus projections) during their team-controlled years:

- Andrew Benintendi: $80 million through 2022

- J.D. Martinez: $79 million through 2022

- Mookie Betts: $58 million through 2020 (!)

- Eduardo Rodriguez: $36 million through 2021

Doing some simple arithmetic, you can see that Benintendi, Martinez, or Betts would more than offset the negative value of Price's deal (meaning the Sox would have to add positive value on their side) while Rodriguez would more or less even things out on his own.

In more practical terms, these deals are pretty much even:

- Price + $42 million for negligible prospect; Boston saves $54 million

- Price + Rodriguez + $6 million for negligible prospect; Boston saves $90 million

However, getting one of Boston's bigger names would mean expanding the package.

Deal #3: The Red Sox want value back

Maybe Chaim Bloom & Co. are reluctant to make their first big deal in Boston a pure salary dump, so they want to get some value back. There are two ways to get there. The first is to add even more money on their side of the deal; the second is to add a player more valuable than Rodriguez.

It’s always tricky to figure out exactly how much a specific prospect is worth to different teams, but luckily FanGraphs has done research that can help us draw up a blueprint. Using that same $11 million/win valuation, here’s how they value prospect tiers:

Position Players

- 55 Future Value (i.e. Luis Robert, Nick Madrigal): $51 million

- 50 FV (i.e. Andrew Vaughn): $25 million

- 45 FV (i.e. Blake Rutherford): $8 million

- 40+ FV (i.e. Zack Collins): $5 million

- 40 FV (i.e. Yolbert Sanchez): $2 million

Pitchers

- 55 FV (i.e. Michael Kopech): $40 million

- 45 FV (i.e. Dane Dunning): $5 million

- 40 FV (i.e. Jonathan Stiever): $1 million

So in theory, a package of David Price + Andrew Benintendi would be worth Andrew Vaughn + Blake Rutherford + Zack Collins. OR, it would be worth Michael Kopech going back to Boston all by his lonesome. Alternately, if the Red Sox suddenly decided they only cared about saving a little bit of money, then Price + $70 million might buy them Vaughn, while Price + $50 million could get them Dunning or Collins.

Obviously, real-life deals aren’t done in the isolation of a Google spreadsheet, but I think it’s fair to draw a couple of conclusions. 1) The White Sox should expect Boston to pay a decent chunk of Price’s salary, especially if no one else is coming to Chicago with him. 2) If Boston is really interested in Andrew Vaughn and/or Nick Madrigal like rumors suggest, then they should be prepared to part with a meaningful asset like Benintendi. 3) The perfect, win-win deal probably lands somewhere between the packages I’ve been throwing around so far.

Price, Rodriguez, and $15 million for Dunning, Rutherford, and a flier seems like the type of trade that would leverage Rick Hahn’s payroll space and not overly compromising the White Sox farm system. Heck, I’d probably even prefer that to Zack Wheeler since it would fill two rotation spots. But both front offices are walking a thin line by trying to compete in 2020 and the long-term, which will undoubtedly make it difficult to find a fair balance.